|

|

Nature Bats Last: A Talk with Timothy EganInterviewNick O’Connell

Timothy Egan. Photo by Sophie Egan. T imothy Egan is one of the most gifted and imaginative interpreters of the American West. With a journalist’s appetite for research and a novelist’s eye for the telling detail, Egan has defined the region for a national audience. He worked for 18 years as a reporter for The New York Times, first as the Pacific Northwest correspondent, then as a national enterprise reporter, earning a Pulitzer Prize in 2001 as part of a team that wrote the series “How Race Is Lived in America.” He currently contributes to the newspaper’s Outposts column.

He is the author of The Good Rain (1990), Breaking Blue (1992), Lasso the Wind, Away to the New West (1998), The Winemaker’s Daughter (2004), The Worst Hard Time (2005), a nonfiction account of The Great Depression's Dust Bowl, which won the 2006 Washington State Book Award and a 2006 National Book Award. His forthcoming book, The Big Burn, chronicles the devastating 1910 forest fire, which incinerated a huge swath of the inland Northwest while paradoxically ensuring the survival of the idea of conservation. (Read an excerpt from The Big Burn in this issue of The Writer’s Workshop Review.) Egan lives in Seattle with his wife, Joni Balter, and their two children. The interview took place on the deck of his home in the Seward Park area with the Cascade Mountains looming in the background. Surrounded by cedar trees and chirping birds, the fit, trim, 55-year-old writer bubbled over with ideas, energy and enthusiasm, as effervescent as a bottle of well-shaken champagne.

How did you come to write The Good Rain? Then a new agent picked up the clients of the woman who had been hit by the bus. The agent said, “This novel shows some strength, but it’s not going to work in the present environment. What else do you have?” “I’ve been thinking about the Northwest in a different way,” I said. I was just starting to work for The New York Times and was forcing myself to look at this area as an outsider, instead of a third-generation native. What year was that? I proposed The Good Rain as a 10-page outline and sold it to Alfred Knopf. I got a wonderful editor named Ash Green, an old-school, gentleman editor, a terrific guy, who’d been there 40 years. His son had moved to Oregon and he was curious about this region. I was chasing Theodore Winthrop, who was about my age. He was 33 when he died, the first American officer killed in the Civil War. I was young and exuberant, like the guy I was following. You can see the spirit of youth in it. When did you start writing? There are a few ways you can do this: the starving poet route is absurd; you can’t make a living. And I’m a public person; I like to be involved in politics and events of the day. So journalism was a clear path: for a person from a lower middle class background, it was an instant entree into society. I could call up the governor, the mayor, or a visiting author. It’s one of the few professions where you can have access at a very young age to the power structure and to how things work. The third option would have been to go to graduate school and learn creative writing. I’m really glad I didn’t go that route. I have high regard for people who have come out of that, but your life experience gets so narrow; you end up writing for other graduate students. Being a journalist allowed me to cover forest fires, volcanoes, see people who were starving to death, be in the middle of a riot, be in a trial when the murder verdict is read, see the expression on the face when someone loses a loved one. You can get all these life experiences with journalism; you can’t get them in graduate school. So very early on I realized that journalism was a path to getting experiences to write about. What part did your education play in your writing? Then I went to the University of Washington. I was able to take junior level English classes my freshman year because I had been reading Joyce, Milton and Dante in high school. Before I received my degree, I got on at the Seattle Post Intelligencer. It took me seven years to earn my degree. You know the scene of John Belushi in Animal House: “Seven years of college down the drain!” and he crushes the beer can against his head. That was me because I didn’t get my degree until much later. I started doing night cops down at the Seattle Police Station. I saw dead bodies and all of these awful things. When you’re 23, this is really cool. What was the P-I like back in the '70s? How did you come to write for The New York Times? “You have to pay me more money," I said. “We’ll do better than that,” she said. “How about we hire you?” I’d always heard they never hired people directly. You had to come in through Ivy League schools and then the Metro desk. To hire me directly onto the national desk was almost unheard of. So I owe my The New York Times career to this horrible disaster. What did you learn while you were there? What did you learn from the reporting? How has the newspaper business changed? We joke at The New York Times, “Gee, I wish the moat was back up. They’re all over us now.” It’s good in that you see things that you’d miss, but a large percent of it is ideological, hate-filled, and stupid. These people have their axe to grind and it has nothing to do with what you just wrote. We never had that degree of involvement with the reader. That’s the number one difference. The number two difference is the 24-hour newsroom. The news never ends. Now, you’re constantly updating. The third difference is the huge audience. I used to have an audience of a million readers for The New York Times. Now I have 20 million for The New York Times on the web. The newspaper business has never had a bigger audience. My line is that it’s like the Ford Motor company produced its bestselling car of all time, but they gave it away. We have the maximum audience, but can’t make any money off it. What effect did the Jayson Blair scandal have on the The New York Times? No one knows how it happened. He was going through a pretty elaborate series of ruses to create this fraud. He was having the photographer send pictures to his email so he could describe the place physically even though he hadn’t been there, the brown hills of this or that or the rising tide of the river, with a dateline, but in fact he was sitting two floors above the national desk in Manhattan looking at pictures.

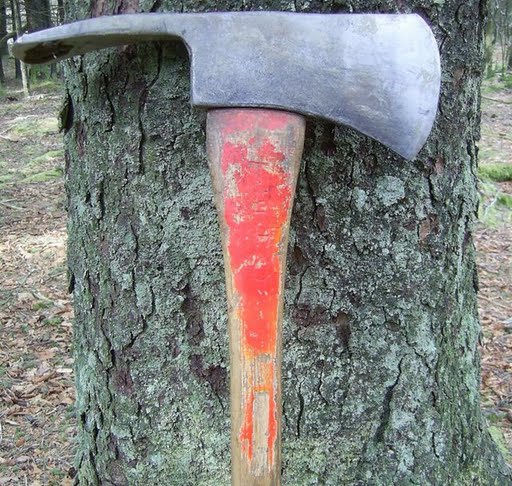

The Pulaski Fire Fighting Tool: Invented by Ed Pulaski and still used by the U.S. Forest Service. Was this a symptom of a larger trend of nonfiction writers fictionalizing their stories, as was the case with James Frey in A Million Little Pieces? Does that make your job as a writer harder? Now, in my nonfiction books I sometimes have an internal monologue, what someone is thinking. And someone will ask in a writing class, “How did you know what he was thinking?” There’s a very simple answer: I asked them. I said, “At the point when the ship was sinking, what were you thinking?” And they said, “God, I was going to lose my wife.” They gave me this very detailed answer. So then you can reconstruct, based on reporting. So I can say, “As the ship went down, he was thinking about his wife.” Not because I’m projecting as McGinniss did, but because I asked him. It’s really simple. Reporting, reporting, reporting--that’s what brings nonfiction to life. That’s where Frey and others really tick me off. They drag down a well-thought of genre. Where did you get the source material for the dialogue in The Worst Hard Time? How much interviewing and library research do you conduct for a nonfiction book? So I read a ton of stuff. Firsthand stuff is the best: diaries, oral histories. Then I do what a lot of academic writers don’t do; I immerse myself in the place. I want to smell, taste, touch. I want to live there for a while, see what the weather’s like, the food, the dialect of the people. I can only get so much from the page, and then I try to throw myself into the place. So it’s a two-part deal; the intellectual immersion and the physical immersion. And then I start to look for the narrative arc. With the Dust Bowl book, I would sit in a circle of a dozen people in these little towns in the Texas Panhandle, listening to these charming 85-year-olds. I’d be running my tape recorder and listening to these incredible stories about what it was like to be 18 years old when the sky turned black at noon. Then I’d go back to my crappy hotel room with deer blood on the rug and replay this stuff and start to see the story. That’s one thing you have to trust to serendipity; I go into this thing not knowing what the story line is. I end up cutting a lot after I see the narrative arc. The fear is that you don’t see the narrative arc; if the story doesn’t emerge, you’re toast. I look at events in a storytelling arc. In the fire book I saw it as the founding myth of the Forest Service: these martyrs who died gave them a foundation that allowed conservation to become an American ideal. The Forest Service had mythologized it too, it was their sacred text. We need these stories to run our lives. Lasso the Wind is a search for a sustaining story of the West. What holds us together as Westerners? So I interviewed a ton of people and ended up dropping what doesn’t fit my ultimate story. I don’t want a he said, she said. I don’t want a phone book of episodic oral history. I’m looking for beginning, middle and end. I want things to happen. I want the reader to see change. All the things you want in fiction. So it’s nonfiction that reads like fiction. Where did you get the idea for The Big Burn? As I was finishing the Dust Bowl book, I was looking for something. I didn’t consciously think I’ll go from dust to fire, working my way through the elements, but I like stories when nature is the determining event. With the Dust Bowl book I had living survivors. Most were in their 80s and 90s, a fantastic opportunity to do firsthand history, to look in their eyes and say, “Tell me what it was like.” In the fire book, everyone was gone, so I didn’t have the immediacy you get with survivors, but I had fantastic stuff from the Forest Service documentation of those early days. What was your source for the opening scene of the book? The Wallace stuff came from newspapers. The national press covered this fire so there were about a half a dozen contemporaneous newspaper accounts of the evacuation. So it came from Forest Service records and contemporary newspaper accounts. Was Ed Pulaski essential to organizing the book? Why are ecological themes so important to your work? How does the region influence your work? I was interviewing the theater director, Dan Sullivan, and he said, “In a dark place, people like to go into caves and tell stories.” That’s certainly why we’re such a great book town. In the winter, you can get 500 people at a reading on a Tuesday night, which is almost unheard of in other American cities. This town embraces its writers. You have to go to other towns to realize we’re unique in this regard. What do your books say? Is there one theme that runs through them? Is this true of The Big Burn, too? What other books do you have planned? Is it nonfiction? Anything you’d like to add?

|