R

ichard Hugo is a ghost haunting the landscape of White Center. Although he is the town’s greatest literary figure, his memory is neglected. There’s nothing in White Center that would give you any clue that Hugo grew up and began writing poetry here. In a 2009 blog article, “Searching for Richard Hugo in White Center,” local writer Brian James Barr lamented the fact that there is no plaque, statue, or even a photo on the wall of the Triangle Pub to commemorate Hugo. Not even Hugo’s childhood home remains; it was torn down years ago, replaced by a church parking lot. Troubled to find no trace of Hugo here, Barr urged others to help him find a way to honor Hugo’s legacy.

Prior to reading Barr's article, I knew little about Hugo, except that he was a Montana poet originally from Seattle whom I might have read in college, and that Richard Hugo House, a Seattle literary arts center, was named after him. That was it. But I call White Center home these days, and Barr’s article piqued my interest. Who was Richard Hugo? What is his White Center legacy? And where, if anywhere, would I find it?

Although you can't find much about Hugo in White Center, there's plenty online: poems, articles, literary criticisms, enough to put together a sketch of his life. Hugo was born Richard Hogan on December 21, 1923, in White Center, Washington. His father ran off when Richard was young; Hugo later took his stepfather’s surname. He was raised by his grandparents, a severe couple who provided Hugo with little in the way of love or emotional support. His childhood home was on a gravel street just a few blocks from the center of town, a seedy area known mostly for hard drinking and fighting. Hugo enlisted in the Army Air Corps and served as a bombardier during World War II, completing thirty-five combat missions. After the war, he studied writing at the University of Washington, married, and took a technical writing job at Boeing. Hugo's first book of poetry was published in 1961. Soon after, he quit Boeing and took a teaching job at the University of Montana. His wife abandoned him in 1964 and they divorced; Hugo remarried in 1974. Hugo was a heavy drinker; he quit drinking for a spell after his second marriage but took it up again. He died in Seattle in 1982, at age 58, of leukemia. Hugo House opened in 1998; it is the nearest thing to commemorate Hugo’s ties with and importance to his original hometown, but its location is miles away from White Center, both literally and figuratively.

As a poet, Hugo is known as a regionalist, a Montana poet who described himself as “a poet of rivers and trout.” Many of Hugo’s poems are about depressed or abandoned towns, desolate landscapes, and the people forgotten or lost within them; they often speak of loneliness and resignation, anger and despair. In his poetry, "Hugo gives us...an image of the town seen from its underside...a town populated by drunks, angry boys, lonely travelers in bars...," wrote Michael Allen in

We Are Called Human: The Poetry of Richard Hugo (University of Arkansas Press, 1982, 16), aptly describing the White Center Hugo grew up in, a town that hasn’t changed all that much since Hugo was last here despite what some people might tell you.

One rainy day in March, I went out to see what I could find of Richard Hugo. I found his childhood home, now an asphalt parking lot sagging down to 15th where the house once stood. The old holly tree is still there; an unkempt cherry tree stands along the back fence. Two women drove through the parking lot and went into the church, eyeing me suspiciously. Could they guess why I was loitering in the parking lot, touching the rough cherry bark, inspecting its green buds, looking up at the holly tree, imagining Hugo looking east from where the front porch used to be toward the wooded hill to the east, taking in Hugo’s last look of the place he described in “Doing the House,” in which Hugo anticipates and even seems to approve of the old house being torn down? "This will be the last time. Clearly / they will tear it down, one slate shingle / at a time...." (

Making Certain It Goes On, 325).

It's easy to understand Hugo’s lack of attachment to the old house. The house was a lonely, isolating place for Hugo, a “loveless shack,” according to Hugo’s friend, Annick Smith (

Crossing the Plains with Bruno, Trinity University Press, 2015, 6), on a “lonely country road...a road that nobody ever came by on,” as Hugo recalled it in the film,

Kicking the Loose Gravel Home (Smith/Ferris, 1976). His grandmother was “very erratic in her attitude toward men,” according to Hugo, at times “vicious and cruel”; sometimes there were “gratuitous beatings.” His grandfather was, at best, indifferent. As a child, Hugo assumed he had been left there because his mother didn’t want him. In fact, his grandmother wouldn’t give him back. It is no surprise that Hugo had feelings of inadequacy and depression, or that home—this home—was always a place Hugo wanted to get away from, physically and emotionally. "Clouds. What glorious floating. They always move on / like I should have early" (“White Center,”

Making Certain, 375).

Despite rumors of its impending gentrification, White Center is still "tough," still "at the edge of civilization" (terms Hugo used to describe it), still haunted by sad characters who smoke and drink and loiter outside bars too early in the day, mostly working class tending toward unemployed with a thriving homeless population. The bums aren’t whistling “Painting the Clouds with Sunshine” these days; they are more likely to be drug-addled zombies shuffling aimlessly along from alley to alley. The garbage cans on 16th seem constantly full to overflowing, empty soda cups, pizza boxes, vodka bottles, and disposable diapers scattered on the sidewalk, liquor license notices taped up in every vacant storefront, the skunk smell of marijuana wafting down every alleyway. The town center reliably produces at least one murder, shooting, or stabbing each year. I guess that’s what they mean when they say White Center is “gritty.”

White Center’s essential character hasn’t changed much since Hugo last lived here. It is more ethnically diverse, sure, but its poverty level is more than twice as high as the county average. It is still downtrodden, still a town of drunks. You see them spilled out on the sidewalk outside bars in the afternoons and evenings, characters seemingly suspended in time from Hugo’s day, factory workers and retirees, honest drunks, halfway into their five bourbons, down to their last cigarette, the denizens of the real White Center.

By his own admission, Hugo drank too much and spent a lot of time in bars; for a period of his life, he called them home. In Kicking the Loose Gravel Home, a film that documents Hugo's return home in the 1970s, he mentions two bars: the Swallow and the Triangle. The Swallow is long gone, but the Triangle is still there, a couple of blocks from the old house. On my walk back from the parking lot, I venture in for drink in Hugo’s memory, to see if there’s a picture of him on the wall. There isn't.

“Get you a drink?” asks the owner, Geoffrey “Mac” McElroy. Mac is this year’s honorary mayor of White Center. If anyone knows what is happening in White Center, he does. He pours me a bourbon and we talk about gentrification, the Starbucks going in, the proliferation of trendy new bars down the street. He doesn’t seem concerned about the competition. There have always been plenty of bars in town, he assures me. It has always been “gritty” here, “rough and tumble,” “edgy,” an “active place”—buzzwords for a place that's ripe for gentrification. People have always come to White Center to live a little at the edge of civilization. The new bars might be a little more upscale, backed by a little more money, but they are nothing new.

A film crew recently picked the Triangle Pub as the most ’70s bar in Seattle. Maybe it’s all the neon. A red glowing FOOD sign hangs crooked above the kitchen doorway; another red sign glares COCKTAILS from above the booze. I’m not sure this would be Hugo’s kind of place now, but there's hope: Tuesdays are open mic night at Mac’s; they sometimes have poetry readings, which could make the Triangle Pub the most literary venue in White Center outside the library. I ask Mac about Hugo. “The poet,” he answers, “sure.” Would he hang a picture of Richard Hugo in the bar? “Absolutely,” Mac says. “In fact, if you bring me a picture, I’ll even frame it.”

In his autobiography, Hugo wrote, “New businesses and many new people have moved into White Center...and one White Center restaurant is reputed to be pretty good” (

West Marginal, 29). The same could be said of White Center today; many new people and businesses have moved into White Center lately, mostly bars and restaurants drawing in a new crowd. This is nothing new; even forty years ago, Hugo called White Center “just another suburb.” White Center’s version of gentrification has been going on for years, and hasn’t displaced anyone, not yet. The town is a cultural melting pot, with a large Hispanic, Asian, and East African population supplementing the historically black and white citizenry. Minorities still own and run most of the businesses, but things are changing. Seattle wants to annex the town and turn it into another soulless urban hub. Investors are buying up property, waiting for the zoning to change. White Center lacks the tax base to incorporate and save itself from all of this progress. The town hasn’t hopelessly changed for the worse, not yet, but there’s a Starbucks here now. How much longer can it hold out?

Most of Hugo's best-known poems are not about White Center, yet the more I read of Hugo’s poetry, the more I realize his poems are as much about White Center as any other place, perhaps more so. In “Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg,” Hugo seems to have imposed his childhood home upon a derelict Montana mining town. According to Nicholas O’Connell in

On Sacred Ground: The Spirit of Place in Pacific Northwest Literature (University of Washington, 2003), Hugo used Philipsburg “to acknowledge and overcome his feelings of inadequacy and loss...to resist the depressing hold that the town exerts over him” (122). But really, wasn't White Center the town that exerted the depressing hold on Hugo? Hugo only visited Philipsburg on a Sunday on a whim; he spent just a single afternoon there and wrote his poem the next morning. He lived in White Center for twenty-five depressing years, always longing to get away.

The psychic presence of White Center appears in other Hugo poems. "Did you park at that house, the one / alone in a void of grain, white with green / trim and red fence, where you know you lived / once?" ("Driving Montana,"

Making Certain, 204) Hugo’s childhood home was a white house with green trim and a red fence, the only house on the block until the war, a lonely place in Hugo’s mind made lonelier when imagined “alone in a void of grain” alongside a Montana highway. This reminiscence suggests, as O’Connell notes, that Hugo aired his grievances obliquely, objectifying his feelings “by finding the physical equivalent of them in rundown [places], the objective correlation to his inner psychological state,” that allowed him “to gain critical distance on such feelings, permitting him to write about them without sentimentality” (121).

Although Hugo wrote his earliest poems in White Center, he went elsewhere to find them, to the Duwamish River, a decaying landscape at the edge of a polluted river flowing through Seattle’s industrial district. "Why did I have to go to the river to find the poems?" Hugo wondered. "Why not around White Center, the district I knew so well?" Because, he realized, once he got away from home, he got closer to himself (

West Marginal, 11). Had he tried to locate his poems in White Center, he feared, certain feelings that he had about himself would have gotten in the way (17-18).

"For years I was never poet enough to do much with White Center," Hugo wrote. "My attempts at poems about my hometown seemed blocked by allegiances to memory. That was the trouble: they were about White Center. The imagination had no chance in the face of facts" (25, 29).

Still, Hugo wondered what his poems would have become if he had continued living in the old house. "I'd always entertained the idea that had I bought the house from my mother and aunts and remained there alone my writing would have been different," he wrote. "I fancied that I would have written less but better. My poems would have been wilder, perhaps longer" (177).

“Don’t be foolish,” Smith had told him. “If you’d stayed there, you would have quit writing years ago” (179).

Despite his feelings about White Center that drove him to Montana to find himself, Hugo had sentiment for the old house. “There’s something about houses,” he said in

Kicking the Loose Gravel Home. “There’s one we always think of as home, then all the rest are just houses we live in. And if that’s true, then this is the one for me.”

I know what he’s talking about. I grew up in a suburb of Seattle, in an old house that was torn down to make room for the freeway. I am not sad it is gone; it was not a happy place. I moved there after a bitter custody battle. I got to see my parents at their worst, and felt that it was somehow my fault. My stepmother had “anger issues,” and I was often the target of her abuse. Like Hugo, I retreated into my mind, into drawing, writing, music, then later, as soon as I could venture off by myself, into the world, walking or riding my bike all over the city and out into the mountains, as far away as I could get some days, in no hurry to get home even if there would be hell to pay when I came in late. I could not wait to move away, and vowed to do so as soon as I could. To say I hated that house would be an understatement; still, it is the house I grew up in, the house I consider home—or did, until they tore it down. I find myself returning to the old house sometimes, even though it’s gone, standing where the driveway used to lead down to the old house, imagining myself climbing the big cedar and oak trees that are no longer there, playing baseball in the vacant lots now occupied by mansions with my brother who died years ago. I don’t know why I return; there’s nothing there now but a sense of loss, loss I imagine is mine alone to feel. Who else comes here to look for these things? Who else would know what has been lost?

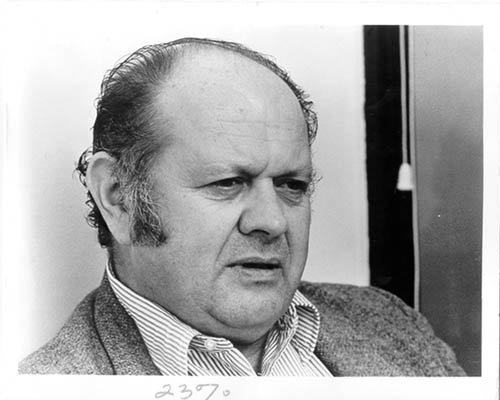

On my way back from the Triangle, I venture into the Locker Room, a dive bar down the block, to see if there's a picture of Hugo there. The bar is intimidating even from the sidewalk; it smells of stale beer and cigarettes, nicotine still leaching out of the walls from decades ago. I hesitate; it is clearly not my kind of place, but I go in anyway. Busch beer on tap is $1 a pint; they go through eleven kegs a week the bartender tells me for no apparent reason. A woman sits down next to me; she orders a Bloody Mary and a packet of beer nuts for breakfast, and starts telling me about her cat. I feel like a regular already. I order another bourbon and look around. It's dark in here, somber; the dozen or so patrons mostly sit quietly, alone, nursing their beers. The bartender engages them in conversation as they come up to the bar, one at a time, dollar bill in hand; she knows them by name, knows their story, but loves them just the same. There are pictures of departed patrons tacked to the wall, but no photo of Hugo. Still, I can envision him here, a balding, bear-like man sitting at the bar, drink in one hand, cigarette in the other, starting a conversation with whoever might sit down, telling a story, making a joke, laughing his infectious laugh. This, I think, is Hugo’s kind of bar, devoid of pretense, inhabited by the “forgotten people” Hugo most identified with (Smith, 7). It may well be the last outpost of Richard Hugo’s White Center, a place he could have called home.

“Nothing dies as slowly as a scene,” Hugo wrote in “Death of the Kapowsin Tavern” (

Making Certain, 102). Such was Hugo’s remembrance of White Center: a dying scene, to which he returned once more before he died, to find the old house gone, things remembered no longer there. "Where the house was / is now a church parking lot..../ Today you found it all gone. / You heard nothing to remind you how it had been" ("Where the House Was,"

Making Certain, 430). The White Center scene is still slowly dying; perhaps it always will be. How long before the last trace of the old White Center is gone, before the Locker Room goes broke selling $1 pints, before the town is annexed by the city and the five-story multiuse projects start breaking ground and the essential character of the town is hopelessly lost? Not long, it seems, but even this is nothing new.

"One nice thing about America is that you're always losing," Hugo said in a 1981 interview (Gardner, 145). "They're always tearing down something you love and putting something uglier in its place." So it goes with White Center, although to be honest, the new Starbucks isn’t as ugly as the gas station they tore down, so perhaps all hope is not lost. In fact, things might be looking up on the literary front, too. Hugo's poetry has been described as "a medium through which we are notified that something is disappearing...by reminding us of what we are continually losing" (Don Scheese, "The Presence of Space in Richard Hugo's Montana Poems,"

Iowa Journal of Literary Studies 6, 1985). The "ongoing, rapid economic and social facelift" of the American West "provided Hugo with plenty of material for his poems" (Scheese, 53). There's hope, then, that the impending, final death of Richard Hugo's White Center will provide rich material for some future poet to remind us of what has been lost.

In the meantime, Hugo’s White Center legacy goes unnoticed and is largely unknown, but it hasn’t been erased, not completely. Even if nobody has put up a plaque, statue, or picture of Hugo on the wall of any tavern in town, shreds of Hugo’s past endure in White Center if you look closely. If you walk along Hugo's childhood street and sit down on the grass next to the holly tree and listen, you might hear neglected sounds that remind you how it had been: a robin singing from the cherry tree, bees buzzing in the clover, kids playing down the street, a dog barking on the next block, a train horn wafting up from the Duwamish River valley like a siren’s song calling you down there. If you wander a few blocks over to Hugo’s “Fourth Hill,” you can still look out across the Duwamish River Valley to the mountains, a knife edge cutting off the Puget Sound region from the rest of the nation, and feel what inspired Hugo to seek to escape into the unseen, psychic space beyond those shining mountains, to seek refuge in poetry.

I found a suitable photo of Hugo and gave it to Mac, who threatens to frame it in neon (“to give these people some class,” he says, winking). By the time you are reading this, it will be up on the wall of the Triangle Pub. There was even a recent poetry night dedicated to Hugo. Still, I imagine a reflecting pond here at the site of the old house would be a more fitting memorial to Hugo. In his autobiography, Hugo recalls with fondness a pool of water that formed in the hollow of an old stump out in the woods behind the house, where he would pretend to fish as a small boy and spent time reflecting. He recalled looking into the pool once and coming face to face with himself, a scene he described with Zen-like clarity: “I saw my face and behind it the sky, the white clouds moving north” (

West Marginal, 163). But while I am standing beside the holly tree after the rain has stopped, I realize there’s one already here, a little pool of water in a slight dip in the parking lot that they haven’t patched over, so shallow you might miss it. If you come here after the rain has stopped, you can look down and see your face reflected in the water and behind it the sky, the white clouds moving north, just as Hugo described it. So maybe Hugo doesn’t need a plaque, statue, or even a picture on the wall to be remembered here. Whatever remains of Hugo’s White Center may be enough to remind us that his spirit still lingers here, waiting to be found by whomever might come looking.