L

awrence Wright has written it all. He’s an author, screenwriter, playwright, and staff writer for The New Yorker.

He wrote the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Looming Tower,

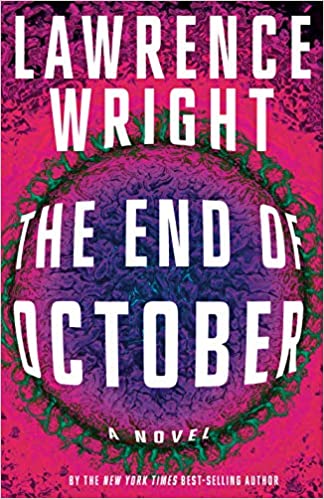

(2006) about the events leading up to 9/11; the novel, The End of October

(2020) about a fictional plague; and recently, “The Plague Year,” a nonfiction piece in The New Yorker

about Covid 19 that he’s turning into a book of the same name. He recently spoke with Nicholas O’Connell of The Writer’s Workshop

about his work.

How did you get interested in writing about pandemics?

I was a young reporter in Atlanta and I did stories about swine flu and Legionnaires’ Disease. Both stories took me to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta. At that time the CDC was nonpareil in the world and the people who worked for it were so smart and noble. You’d see these Harvard-educated doctors and guys that looked like geologists in Arizona with bolo ties. I was crazy about them and thought this was a fascinating area to write about. Disease is both terrifying and commonplace, so we tend not to take it as seriously as we do something like a war. Imagine if we were in a war that had killed 400,000 Americans how different our response would be.

What motivated you to write the novel, The End of October, about a pandemic?

It started as a screenplay for Ridley Scott. He’d read Cormac McCarthy’s novel,

The Road, which is a post-apocalyptic novel, a father and son wandering through the ruins of civilization. Ridley’s question was, “What happened?” Cormac doesn’t bother to explain. I thought that was interesting. What could bring civilization to its knees? A nuclear war would certainly qualify, but how do you find a hero in that environment? My thoughts went back to my early days at the CDC and how many heroes I saw there. I decided I would set the screenplay in that world. He never got around to making it but it was always a story I wanted to tell.

How did the fictional virus, Kongoli, resemble Covid 19?

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccine were both designed by Dr. Barney Graham who designed my fictional virus. It’s an incredible piece of good fortune that I found my way to Barney Graham at the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases. He was well-known in that rather cloistered world and he wasn’t so busy back then. I told him what I was up to and I asked his help in designing a novel influenza. I wanted something that would be like the 1918 flu. October 1918 is still the deadliest month in American history. Barney helped me design it but then I painted myself into a corner because I had to cure it. So he helped me cure it. People like Barney Graham are essentially puzzle solvers. I gave him a riddle and he was delighted to work on it. What a piece of luck and coincidence that he would turn out to be the guy in real life who invented the vaccine that we’re all depending on.

The novel is remarkably prescient.

I want to quarrel with that for a minute. I did the research and talked to the experts and they told me what would happen. It wasn’t like I was a prophet. I interviewed dozens of people in public health and read all the reports the administration should’ve looked at and I just translated that into fiction.

How have readers responded to the novel?

It’s been really gratifying. Starting with Amazon, it developed a terrific constituency and got on the New York Times bestseller list. Probably if I had waited and this pandemic, the real one came along, I would have turned my attention to the real event. But writing the novel prepared me for what was to come.

Did your reporting for the novel help you to write The New Yorker

piece?

It helped get my editor at

The New Yorker, David Remnick, to ask me to write about it. He rightly figured that I already had a lot of sources at my disposal. I had prepared myself by understanding a lot about viruses and how they work. I had the grounding that I needed to go fast on this story. Writing something ambitious like that was a kind of call to arms. I immediately conceived this idea that it wasn’t just a story about the disease; it was a story about America and how we reacted to it.

This is such a big topic. How were you able to put all these pieces together into a coherent story?

In this case, I had a conception. The conception was America through the eyes of Covid 19. I observed that it was not just a story about a disease; it touched on the economy, race, politics, science, everything about our public life. I had to find exemplary figures. I call them donkeys, the beasts of burden that carry all this information on their back and take the reader into a world he might not be familiar with. Fortunately, in the White House I found Matt Pottinger who was incredibly helpful to me. I wanted to get into public health, FDA, NIH, CDC, all these different entities. I had to find my donkeys in each of them. It’s almost like casting, trying to find people who can star in that role.

In The New Yorker story, you talk about the three mistakes that were made in the battle against Covid. How did you come up with that list?

I realized when I ran back over my reporting there were three moments when things could have changed. If we had gone into China and learned there was asymptomatic transmission, things might have changed. If the CDC had not screwed up the test, things might have changed. If the nation and in particular the president had not made masking a political issue, things might have changed. But in each of those cases we failed the test.

Have you dug up anything about the actual source of the virus?

I’m writing a lot about that in the book. That will be our next interview.

How did Washington state politicians figure in the response to the pandemic

I really enjoyed my conversations with Senator Patty Murray and Governor Jay Inslee. They were of great help to me. They did a good job as public servants in addressing this problem early. I really commend the governor and the senator for their help for me and for their state.

In many ways your story in The New Yorker reminds me of your book, The Looming Tower, which examined the U.S. government’s lack of preparedness for 9/11. Do you see a similar kind of government response to the pandemic?

I do. It’s a dismal comparison. One is the infighting among government agencies; agencies don’t cooperate with each other and actually stand in each others’ way. There’s a lot of blame to go around and nobody was accepting any of that. It reminded me a lot of the conflict between the FBI and the CIA that blinded us to the efforts of Al-Qaeda to attack America.

9/11 was one of the greatest intelligence failures in our history, but so was the failure to anticipate the coronavirus. In the novel, I created the virus as a stress on the system. In the novel, it’s a pandemic. You have to understand this past year as one in which the system was stressed. It raised the temperature on all the different factions inside America. The result is the chaos we’ve been experiencing.

Once this is over, what should be done to ensure that lessons are learned and preparations made to prevent a future pandemic?

There are lots of levels to the answer. We actually do need a World Health Organization that has certain powers and is not so subservient to different countries that it is afraid to investigate outbreaks that could become pandemics around the world. I don’t mean to denigrate the World Health Organization but it’s a supplicant. Its powerlessness has been on stark display.

We have to have a national plan. In 2020, just as in 1918, the federal government didn’t have a national plan and the country was going to suffer badly. The federal government left the states on their own. They had no preparation for dealing with an epidemic of this scope. They didn’t have the resources, experience or understanding of what to do. The federal government had all of that at its disposal and failed to use it.

We have to invest in our healthcare systems. We’re the only country in the world that separates clinical health from public health. That makes no sense. We have to have a more integrated system in which the reporting is more focused and immediately accessible. We need to make sure we have enough hospital facilities. The logistical back bone we need right now to get the vaccine out doesn’t really exist. All of this is in preparation for the next big disease, which could be far worse than Covid 19.

Nicholas O’Connell, M.F.A, Ph.D., is the author of The Storms of Denali

(University of Alaska Press, 2012), On Sacred Ground: The Spirit of Place in Pacific Northwest Literature (U.W. Press, 2003), At the Field’s End: Interviews with 22 Pacific Northwest Writers

(U.W. Press, 1998), Contemporary Ecofiction

(Charles Scribner’s, 1996) and Beyond Risk: Conversations with Climbers (Mountaineers, 1993).

He contributes to Newsweek, Gourmet, Saveur, Outside, GO, National Geographic Adventure, Condé Nast Traveler, Food & Wine, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Sierra, The Wine Spectator, Commonweal, Image, Rock + Ice

and many other places. He is the publisher/editor of The Writer’s Workshop Review

and the founder of the creative writing program ( http://www.thewritersworkshop.net).