|

|

The Michelangelo of MeatNonfictionNick O’Connell

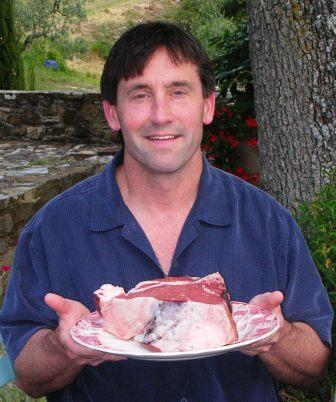

Dario Cecchini shows off his signature cut, Bistecca Alla Fiorentina.

D ario Cecchini raises the cleaver above his head and brings it down hard. Whack! The cleaver slices an enormous steak from a side of beef set on a wooden block in the middle of the stainless steel counter. Whack! Whack! Whack! Whack! With each stroke, he hacks off another prodigious Bistecca alla Fiorentina, his signature cut. Twice the size of a normal T-bone, these are not tiny, tasting-menu tidbits, but thick, mastodon-sized slabs, richly marbled with fat, deep red in color, perfect for grilling.

I move closer to the counter. I don’t want to appear pushy, but I want to get my hands on one of these steaks. The Antica Macelleria Cecchini, located in Panzano, Italy, a lovely hill town 18 miles south of Florence, sells some of the thickest, juiciest hunks of meat on the planet. More than New World in size, Old World in quality, the bisteccas attract salivating carnivores from around the globe. But if you appear demanding, impatient, or--God forbid--insist that he cut one of the steaks in half, Dario will sell you nothing. He may order you out of his shop. Here, the butcher is always right--not the customer. “I am an artisan who seeks quality,” he explains. “I select cuts to offer the best to my customers and put my work in the finest light. Trust in what I suggest.” I nod vigorously, hoping this will advance my cause. Several weeks ago I called from the U.S. and left a voice message about buying one of the bisteccas. When asked about the message, he nods, “Si, Si, Si, Si.” I’m not sure that means he got the message and saved me a steak, or simply that he received the message and now is making up his mind if I’m worthy of one. “Buongiorno, Signora!” Dario sings out to a French woman entering the shop. Despite his curmudgeonly reputation, Dario is a consummate charmer. With his operatic gestures, meat-hook hands, and black hair pomaded up in tiny bull’s horns, he looks the epitome of the Tuscan butcher. The French woman moves into the shop. A competitor? He works his way down the carcass, carving off steaks with practiced skill, exuding the confidence of a man at ease with himself and his craft. He buys what he considers the best beef in Europe, ages it 20 days, cuts it up in traditional Tuscan style, and sells it to adoring customers like myself. His ancestors did this for eight generations. He’s been doing it for 30 years. He must be doing something right. Dario picks up a steel and a knife as big as a machete. He sharpens the knife without looking at it, giving an informal lecture on the correct way to raise cows: grass fed, no chemicals, a good life and killed well, in other words, happy cows. He points to his temple. “Comprendo?” I nod again. It’s impossible to know what’s coming next; another lecture on animal husbandry, singing with the opera music blaring in the background, a quote from Dante’s Inferno, “In the middle of our life’s journey, I came upon a dark wood…” It’s all part of the show—butchering as performance art. “Prego?” One of his assistants offers me a piece of bread smeared with lardo or fat. I sink my teeth into the glistening white grease; it’s salty and unbelievably rich, a long way from the Pritikin diet. He pours me a glass of red wine from a fiasco, a traditional Chianti bottle wrapped with straw, like the ones you see in college dorm rooms with a candle stuck in the top. The wine is strong and good; Dario’s own blend, a bold red Chianti with no new oak, for him the perfect complement to one of his steaks. The French woman approaches the counter on the left, studying the steaks. I return to my post to the right, determined not to get outmaneuvered. Dario trims the fat from the steaks with a smaller knife. Then he stacks them in a line across the counter. They’re so thick they stand on end. “Bravo!” someone cheers. Everyone claps. This is my chance. I’ve traveled 4,000 miles to get one of these steaks. I’m determined not to get outflanked. I position myself directly in front of him. “We can talk about this,” he says, holding up one of the steaks in his enormous hand, “but it’s necessary to taste.” The huge triangle of meat measures 10 inches long, 8 inches wide, 4 inches thick. It weighs 5 pounds and costs $60. A massive T-bone divides the strip loin from the filet. Veins of fat radiate out from the bone. A ring of fat encircles the rest. It looks like something brought down with a spear. He hands me the bistecca and kisses his fingers. “Bellissimo!” “Grazie mille,” I say, taking the prize. “How do I cook it?” He provides a recipe and advice about accompaniments: good company, good bread, and a simple Chianti, nothing recommended by the Wine Spectator. For him, the bistecca is more than just meat; it’s a kind of ritual object, a way of entering into full communion with Chianti. “Buon appetito!” I hurry out of the shop, eager to tell my wife, Lisa, and our German friend Christiane. The owner of our agriturismo, Fabio, has offered to cook the bistecca if I’m lucky enough to score one. He works at Dario’s nearby restaurant, Solociccia, and knows exactly how to prepare it. No Heinz 57! We quickly assemble the meal. The wine store in Panzano suggests a 1997 Chianti Reserva. A shop in nearby Greve provides bread and the ingredients for a Caprese salad: basil, local tomatoes and buffalo mozzarella. We drive back to our agriturismo, a refurbished stone farm house high in the Chianti hills, our Opel Corsa seeming to groan from the added weight of the bistecca. Fabio jumps up and down when he sees the steak. Even he has trouble getting one. He quickly prepares the coals. Once they burn down, he places the enormous slab on the grill. Five minutes per side. Fifteen minutes on end. I listen to the snap, crackle and fizz of fat and inhale the heavenly aroma of carmelizing meat. Dark clouds gather in the south. Lightning strikes in the distance. Thunder booms like artillery. Should we eat inside or brave the weather? We decide to sit outside. We set the table on the terrace framed by cypress trees with a panoramic view of the green Chianti hills. Tiny streaks of light illuminate the dusk. The start of an electrical storm? A mid-summer night’s dream? “Fireflies,” says Fabio, bringing out the steak. We toast to our new friend, Fabio, and our old friend Christiane, whom Lisa met 30 years ago when Christiane enrolled as a German exchange student at the University of Washington. Everything blends perfectly: the bread, the wine, the salad, and the bistecca. The meat is barely cooked and amazingly tender, with a rich, sweet flavor--none of the waxy, lighter fluid aftertaste you get with some supermarket beef. This was definitely a happy cow. We polish off all but the bone. Fabio tells me Dario picks it up and just eats it. Why not? Following the master’s lead, I grab the T-bone and dig in. The meat is even richer and more succulent close to the bone. My fingers greasy and my face smeared with fat, I gnaw the bone till it’s finished and enter into full communion with Chianti.

The author with the object of his quest. D ARIO CECCHINI’S THEORY OF BISTECCA ALLA FIORENTINA

Given that the Bistecca alla Fiorentina (a Florentine-style T-bone steak) is already one of the most supreme physical pleasures in this earthly life, it follows that this dish cannot be “improved upon” nor “modernized,” because it is perfect as is and thus untouchable. Preparation checklist: --A T-shaped bone, filet (top loin) and tenderloin, of mature beef, aged at least 20 days, with just the right amount of fat and not straight from the fridge, standing on a wooden chopping board while waiting for the grill. (This last part is more symbolic than practical, but important nonetheless.) --Hot coals under the grill (use red or evergreen oak), let burn past their hottest point, when a bit of white ash forms on the embers. --Grill low to the coals and the Grill Master ready to begin the ceremony, with a glass of good Chianti on hand for courage and inspiration. --Five quick minutes per side and then fifteen minutes standing on edge. --No salt or other seasoning that would offend this culinary alchemy. --Return to the chopping board, let it stand, slice into chunks and eat! To describe what this pleasure means for a healthy carnivore is impossible. It is to enter into communion with Tuscany itself, sealed with good red wine. After cooking, if you must, you can lightly salt, sprinkle with pepper or bless with a drizzle of olive oil.

NICK O'CONNELL is the author of On Sacred Ground: The Spirit of Place in Pacific Northwest Literature (U.W. Press, 2003), At the Field’s End: Interviews with 22 Pacific Northwest Writers (U.W. Press, 1998), Contemporary Ecofiction (Charles Scribner’s, 1996) and Beyond Risk: Conversations with Climbers (Mountaineers, 1993). He contributes to Newsweek, Gourmet, Saveur, Outside, GO, National Geographic Adventure, Condé Nast Traveler, Food & Wine, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Sierra, The Wine Spectator, Commonweal, Image and many other places. He is the founder of www.thewritersworkshop.net.

|