M

y 11-year-old little leaguer grandson called me to ask why he was unable to find me in the internet. Nothing in Wikipedia even. He wanted to do a school report on a major league baseball player. Me! I was surprised, and a little disappointed with myself that I didn’t have a lot to report.

Most of my life I’ve been teaching American literature with a master’s degree in psychology (not clear how that happened) at a junior college in San Francisco’s Bay Area. I also coached the ladies’ softball team for almost 40 years.

I really was a professional baseball player. When I think about it now, it’s as if I read a story about someone else. I spoiled a perfect game in the World Series in the bottom of the ninth inning against the New York Yankees in the early ’70s.

In high school, I was never considered a pro prospect, but I did get a small scholarship from the local state college, and worked part time at a Safeway grocery store. I bought a car and discovered that the girls like guys with cars. My grades turned crummy and I was placed on academic probation. In the ’60s, if you weren’t going to school full time, married or supporting a mother and siblings, the draft board old ladies would get you, then off to Viet Nam you would go. Not an equal opportunity employer, the military. No fat, no blind, but low IQ is okay. I was faced with the prospect of trading in my baseball bat for an M16 combat weapon. My father suggested I check to see if the Army still had a baseball team.

To play ball in the Army, I had to join for three years and agree to go to Army school for training as an electronics technician at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. A no-brainer. New Jersey trumps Viet Nam every time. I discovered I loved playing baseball while in the Army, and that I was really good. Second base was my spot. Other infielders had stronger throwing arms, but no one had a better glove than the little guy from California’s Bay Area. We played national teams from Japan, South Korea, Australia, Taiwan, and Europe.

For years, I strengthened my forearms during down time in the Army with weights and by squeezing a rubber ball. I must say I had forearms like Popeye, which allowed me to swing a heavy 33-inch bat faster through the zone. I could hit singles and doubles all day. A scout from the new Montreal Expos signed me up three days after I was discharged. I was going to get paid to play a game I would play for nothing. Could life be any better?

After two years on the Triple-A team in Fort Lauderdale (the humidity was unbearable), I was called up to the big team. Management told me they needed my glove and my outstanding speed to help the team get to the World Series.

Our team made it to the World Series and we were playing the infamous Yankees. It was a fun year but I had a disappointing season at the plate. The major league curveball gave me fits. It was game six at Montreal stadium. Yankees one, Expos zero. Bottom of the ninth, and the Yankees needed one more win and they would be world champs once again.

I didn’t start on that cool, breezy, overcast gray afternoon but was sent in for defensive purposes in the eighth and came to bat second. Juan Blanco, aka John White, led off and took a called strike three fastball down the heart of the plate. The 26-year-old Yankee pitcher, Dave Shoupe, needed two more outs to win a perfect game no hitter in this World Series. The only perfect game in major league history was way back in 1956 by Don Larsen.

Shoupe was six foot six and 185 pounds with a right arm that seemed to be six feet three inches long, a real knuckle dragger. The guy was a freak. He had to reach up to put his hands in his pockets. Old Shoupe could reach halfway to home plate, it seemed, before releasing his 100-mile-per-hour fastball. All the players referred to him as The Orangutan. Like the primate, he had a short torso, but he did have long legs unlike the orangutan and sported a thick orangutan-orange Fu Manchu mustache that extended about three inches past his long chin. He would wax it into points like orange fangs. Everyone in those days had long hair…. Not Dave Shoupe. He shaved his head before leaving the locker room on the days he pitched. Shoupe was the best pitcher in baseball that year.

My name was announced, “Number 24, Roy Williams!” How have I lived without hearing that every day? The adrenaline button was punched and I became Maximus, the unconquerable gladiator. A rush like that today would explode the old aorta or, worse yet, a paralyzing stroke.

On my way to the plate, I passed Juan and could hear him mumble something about bullets in Spanish. I joined the catcher, young Therman Munson, who I disliked, and the umpire, Emmett Ashford, I greeted with a “How you doing, Ash?” Gave my bat, Vera, a kiss on her sweet spot, then took my stance in the right-hand batter’s box as I had done a thousand times. On this day, I was wearing my tight-fitting mock turtleneck undershirt feeling like I was in Fort Ord again in cool 60 degree Monterey, California. I felt good and powerful, and I was determined to do my part: get on base, spoil the no-hitter with a strong line drive to the alley between the center fielder and the right fielder, steal second, then score the tying run.

Shoupe completed his ritual on the mound, wetting his fingers while his back was turned to home plate, then rubbing the ball with both hands. Vera Brown and I were ready. I had three bats of different colors: Vera Brown, Vera Black, and my blonde bat, Vera White. The black bat was for night games, the blonde for day games, and brown for weekend games, day or night. It was my routine, but I was never superstitious, just a thing I did. If I broke a bat, the life force of Vera would be in the new bat. To this day, if I pick up a bat, my sweet Vera is with me. No Vera essence in aluminum bats … ever.

Vera was a girlfriend I met while we were in junior college, built like a five foot two Simone Biles. She was a 19-year-old Creole cutie from Louisiana. She had dark skin, long wavy jet-black hair to her shoulders, smooth shapely muscled heavy legs and thighs, a hard tight round butt that women pay thousands of dollars to have, and small firm athletic breasts. Big coffee-brown eyes that floated in the clearest of white, small lips usually uncolored. Her smile revealed white perfect teeth. She would smile at me with sparkling loving eyes. It was impossible for her to take a bad picture. People from India would ask her where in India she was from. A Navy World War II vet once asked her if she were from Fiji. “Are you one of those exotic lovelies from the island?”

My father questioned me if I had met her mother. “She is gonna be a butterball when she gets older, boy. Check her mother out to be sure. Most times they become like the mama.”

While I was away, doing Army duties, she just disappeared. No word at all; no unhappy letters ever. I called her three times a week when away. Never any indication that she was unhappy. Vera lived with her grandparents; they were gone, too. She was from Baton Rouge. That was all I knew about her life before she came to California. As years passed, I think I could have done more to find her. I should have put on my Columbo raincoat, asked the neighbors, gone to her job, and asked a coworker…something. Could I have been too involved in baseball and Army? I used to hope that if I succeeded in baseball, she would be in the stands and send a note to me like in the movie The Natural. It was years before the movie came out. Then I read the book. Ironically, we had the same name: Roy.

Like in the movie’s story, life can be uncanny. I don’t have a single picture of her. A friend of mine took over a hundred pictures of her for a calendar, only of her for each month, dressed in seasonal attire. I had the model. A picture wasn’t important. My photographer friend kept the pictures in his office/garage and lost every photo and negative in a fire before I got a calendar. I had the calendar model, at the time, a picture wasn’t important. Vera and Chaka Kahn, the singer, have the same shy smile. I ran into Chaka Kahn in a YouTube video singing “Ain’t Nobody Love Me Like You Do” from 1983. A message from Vera? It didn’t work out. That is all I have to say about that.

Shoupe began his windup by raising his long right leg over his head like Juan Marichal, but unlike Marichal, he wore white shoes and white long stockings with Yankee pin stripe pants bloused at the knee. All of this white, including the ball, comes at the batter starting out as a blur very quickly. The first pitch was a fastball that started off the plate but crossed at the last split second, knee high.

“Strike one!” Emmett Ashford bellowed as he took a gigantic step to his right while pointing one index finger in the direction of the Yankees’ dugout.

I slowly stepped out of the batter’s box. “Ash! Did you see what that ball did?”

“Just hit the ball, rookie, and shut up,” Munson said after he threw the ball back to the pitcher.

The next pitch was a curve off the plate, low and so far off Munson had to hop over to his right to block it from going to the backstop.

“Ball!”

The ball bounced off the catcher’s chest protector toward my foot. I picked up the baseball to give to the catcher but noticed a dime sized spot of dirt on it. “Take a look at this, Ash. Something sticky like grease is on the ball.”

Munson jumped up and snatched the ball from me. “What you bitchin’ 'bout, Rook?” He threw it back to Shoupe.

“Time!” Ashford yelled while raising both his arms over his head. The stadium was so quiet you could hear Emmett Ashford’s footfalls as he marched to the pitcher’s mound.

Therman Munson spoke to me while he smoothed the dirt in front of the plate with his foot. “What are you doing, Roy? The man is pitching a perfect game. Dude, you’re messin’ with his perfect game.”

I ignored the catcher. I very much disliked catchers, almost as much as pitchers.

“Let me see the ball,” the ump asked the pitcher.

“What you doin’ out here, Ash? Damn! He’s a rookie, man, you can’t be serious.” Shoupe handed the ball to Ashford’s out stretched hand. The fans realized the pitcher was being questioned about a spitball. They cheered and booed loudly. Both dugouts were on their feet. “This is bullshit, Emmett. The rookie got you screwing with me. You know me. I don’t need to do no funny crap.”

“Looks like Vaseline on the ball, Dave. Let me see your cap.”

“I put leather honey on my glove, Ash. That’s leather honey! For gosh sakes, it got on the ball,” Shoupe said as he gave his cap to the ump.

After checking: “Looks really sweaty for a cool day, Dave. Just keep your hand away from your head.”

Ashford threw the Vaseline ball to the ball boy then took his position. “Play ball!”

The next pitch bounced to the catcher a foot in front of the plate. Shoupe screamed into his glove as he stomped around the mound like a crazy person. Munson and their manager, Ralph Hulk, ran to the mound after calling time out to compose the crazed red-faced pitcher.

There are so many variables in baseball, you have to think at least three pitches ahead like a chess match. I loved it. Baseball is very different from football or basketball or soccer. I compare it to tennis, one-on-one, pitcher and batter. The opponent offers the ball to you, not a pass from a teammate. Jimmy Connors vs. John McEnroe, Joe Frasier vs. George Forman.

The next pitch missed low, a curve. “Ball three!”

Now I had a big advantage over the pitcher. I was an old rookie having played the game for almost 15 years. I didn’t think Shoupe knew anything about me. He was the best pitcher in the majors, and I was just a rookie unfamiliar with major-league pitching. I moved a couple of inches closer to the plate knowing he didn’t want to hit me or walk me. He was working on a very rare World Series perfect game and must keep me off the bases. By me crowding the plate, Shoupe had to get the ball over the outside half of the plate. I should get a 100-mph fast ball, his best pitch, over the outside corner of the plate. Not that difficult a task for Mr. Shoupe. If he were to get a World Series perfect game and the Cy Young Award in the same year, he would be a shoo-in for the Hall of Fame.

Vera felt good to my ungloved hands. I envisioned I’d deliver the sphere to right field and as hard as this guy could hurl, all I’d have to do is meet the ball square on Vera’s sweet spot to get a hit.

The Yankees’ infielders shifted more to the right, the thing to do if the pitcher is trying to work the outside corner. The second baseman was on the grass in shallow right field. The scene was set. Hitting was so much easier when you knew where the ball was going and the speed. Even Howard Cosell would be a good hitter knowing those two things. Shoupe performed an unusually speedier windup. It was very quiet. I was totally focused on that long right arm and the ball. With an earsplitting, out of character, karate scream, the baseball flew from those long fingers high and inside as I leaned, ever so slightly, over the plate.

I gave an assignment to my students in a history of journalism class years ago, and received a paper from a student that found a report from a war correspondent during the Civil War. The author described how he could see and hear, from a high ridge at sunset, the marble-size lead musket balls flying through the air in the late evening sunlight, cracking bones and thumping into torsos, including skulls, each with their unique sound. That paper brought to mind that day at the plate.

The ball came in so fast it screamed like I’ve heard many times before but only after being hit with a bat into my glove, never before from a pitched ball. I’ll remember how it screamed at me for the rest of my days. It had to be way over 100 miles per hour. The baseball hit the bill of my helmet, spinning it off my head like a Frisbee before I could react. I went down on my back to the “ahhs” of the crowd.

The catcher was standing over me waving and screaming like I was Sonny Liston and he was Muhammed Ali. “He’s out, Ash! He didn’t try to get out of the way. Call him out, Ash!” Thurman, in all his catcher’s gear, jumped up and down like an unhappy two-year year-old.

I stood up and felt wobbly so I bent over with hands on knees and remembered sweet Vera was there on the ground with her lovely Louisville Slugger logo smiling back at me.

Tom Davenport, our manager, ran out with the trainer. Tom went toe-to-toe with Ashford trying to convince him to throw Shoupe out of the game while the trainer checked my head. I was okay. The perfect game was ruined. I didn’t ruin it. Shoupe hit me in the head and ruined his own perfect game. He quick pitched me and lost control of the fastball, I guess. I trotted to first a little woozy. No way would I ever have expected being hit.

Our first base coach, Hector Luque, met me at the bag,. “Shoupe is crazy mad at you, amigo. Nobody ever say he have the spitball. I think he try kill you, hombre.” Luque put his arm around my shoulder and spoke quietly. “He have no more good mind. He muy loco. Maybe he throw loco ball over here, too. You go second base easy.”

I have no idea when pro athletes graduated from Jack LaLanne power drinks to steroids. Shoupe was acting as if he was experiencing a major ’roid-rage episode. He kicked his glove and screamed garbled sentences laced with profanity. The catcher and the other infielders had to calm the veteran player down and get him back to the mound.

Pitchers will do anything to get you out. You can’t help but hate them. Baseball etiquette states that when a pitcher is pitching a no hitter late in a game, the batter never bunts for a hit. No etiquette for pitchers seems to exist. They never apologize if they hit you. Even a boxer that hits his opponent low apologizes. What makes a pitcher that can’t hit a baseball and plays twice a week so arrogant? Catchers were pitcher enablers. I hated them both.

Our next hitter was Eddie “Bam-Bam” Carroll. Eddie, our third baseman, was at the plate with just five home runs in the regular season, slowly rotating his big bat over his head while waiting for Shoupe’s pitch. I confidently moved off the bag with the knowledge that I had a green light from the manager to steal second base if I felt I could. With a man on first, Shoupe pitched from the stretch, which makes it more likely to pick the runner off at first base. He made two throws to first trying to keep me near the bag. The noise from the crowd was deafening. I took off like a greyhound while Shoupe was in his motion and made a perfect hook slide into second just as the ball came in perfectly from the catcher. The tag was late. The pitch to Eddie was a called strike.

Bam-Bam Carroll hit the next pitch over the center field wall. The center fielder never took a step as he watched the ball soar out of the park into the upper deck. I brought in the tying run and was greeted at home plate by my team mates. Eddie brought in the winning run. Game over. We were jumping up and down taking turns hugging teammates.

The next day, we played game seven. The Yankees became World Series champions on that cool damp Sunday afternoon in October.

The New York press demonized me after the series. They reported I used unfair tactics by asking the umpire to check the ball while Shoupe was nearing a perfect game. A new rule was added to the book, the “Roy Williams Rule.” To quicken the pace of the game, no player shall ask for the baseball to be checked. To quicken the pace? Give me a break. What pace are they talking about? There is no clock in baseball.

I began the next spring in the humid Triple-A league in south Texas again. I had to remember to add antiperspirant to my grocery list. Dripping wet while playing baseball was very unpleasant for me. I still loved the game and felt I would be called up to the big team soon or be traded to a team that needed a second baseman. I was having my best year ever but no calls, and my attitude began to change from the happy-go-lucky guy that was as optimistic as a watermelon farmer in the spring to a guy that was beginning to realize the “Baseball Gods” didn’t want him. My future baseball dreams were in decline.

It had to be that my head got in the way of a Dave Shoupe fastball. The league must have had plans for big Dave Shoupe and I spoiled them. Shoupe won five games the year after hitting me and never won more than six games a year the rest of his career. My bad? I believe he did serious damage to his pitching arm throwing that 100-plus mile per hour karate pitch to my head. The guy had never screamed before while pitching. Shoupe never reported an injury, however. He had a million-dollar-per-year contract for five years that he didn’t want to screw up. I’m just sayin’.

During the national anthem, prior to playing the Port Arthur Oilers in Texas on a hot, clear, humid, stinking-of-Texas Tea afternoon, my life was rebooted. A come-to-Jesus moment, if you will, by an Army staff sergeant singer. All of the Triple-A minor league teams usually get a home-town person to sing to Old Glory. Most of the time, it’s sung poorly, but this time I heard an angelic voice, a powerful effortless tenor recounting the flag still waving at dawn after the all-night bombardment. My pregame concentration was broken by a standing tall Latino staff sergeant dressed in formal Army uniform, medals reflecting the sunlight as he sang into a standing mike near the pitcher’s mound. He had lost his left leg in Viet Nam and was singing without crutches on one leg. The fans applauded and cheered as he approached the end, then he gracefully hopped to the first base chalk line to retrieve crutches from a very beautiful young lady with two equally beautiful little girls dressed in adorable little dresses standing at her side. She kissed him. They hugged Daddy. They were proud of their hero.

Where was I going with my life? What was I doing? I didn’t even have a girlfriend. I turned 26 that summer and was still playing minor league baseball, struggling to get back to the majors. Some of the guys on that team were 18 and 19. A 20-year-old infielder was called up the month before. Getting a call from a major league team, at this point, was now as rare as a Tesla charging in Sandy Point, Texas.

That was my last professional ball game. Ironically, I joined the Army to play baseball to avoid the war in Viet Nam. It took a wounded Army Viet Nam vet to get me to realize the game was just a game and it was over. I didn’t get on the team bus to New Orleans after the game that day. I took a cab to the airport and got on the first plane to California. By the way, they didn’t pay me for July and sued me for breaking my one-year contract.

While at Houston’s Hobby Airport waiting for a flight to San Francisco, I took the baseball program for that game out of my carry-on bag. I opened the program and there he was. A picture of the soldier as a private first class standing in front of an ancient Buddhist temple posing with his M16 weapon along with a bio of the young man. He came to the United States with his parents at 12, joined the Army at 17, lost his leg during the military operation in Cambodia at 18, was fitted with a prosthesis at 19, and allowed to re-up at 20. He acquired his GED and citizenship while in hospital in Houston and was attending Rice University, aspiring to qualify for warrant officer and continue his Army carrier. He had obviously removed his prosthetic leg to make a point while singing the national anthem. Point made, staff sergeant. I got it. Reading his bio only reinforced that I was done with baseball.

I worked full time at Safeway markets while I attended college on the GI bill. Got the teaching job, married my sister’s best friend, and with the help of a GI loan, bought a house.

Returning home from a trip to Las Vegas around 20 years ago, I took my wife on a tour of the now closed Fort Ord Army Base in Carmel, California. We checked into a hotel in Monterey; I called my old friend Willie Mays. Mr. Mays invited us to stop by on our way home the next day so that we might meet the wives.

Willie Mays met us at his front door before we rang the bell. Willie and I shook hands. I noticed how big and soft his palms were and the tender way he held my hand. Still, the big man thick as a young sequoia. Just six feet tall with thigh and calf muscles easily defined through his slacks. Chest still hard and stomach flat. He must have been in his mid-70s back then. Old man body, he called it. Easy to see why they called him Popeye when he was in the old Negro leagues. The thickest wrist I have ever seen. We hugged then checked each other out.

“Put on a few pounds, haven’t you?” Willie said.

“All muscle. You haven’t changed a bit. How you been?”

The question was ignored or unheard. Smiling at my wife he said, “Wow. What has he promised you, young lady? He doesn’t make enough money to be with a beauty like you. Come on in. The wife is outside in the back.”

It was a beautiful June day near the San Francisco Bay with the Golden Gate Bridge visible to the north. We met Mae Mays as she lay on a chaise lounge looking down over the rolling hills with the blue Pacific in the distance. She wore a long lovely white tropical dress with large red and yellow flowers. It was easy to see she was still a statuesque beautiful lady. After being introduced, Mae, with the loveliest smile, asked Willie, “Is she your daughter, Willie?”

“No, honey. She is Roy’s wife. You know I don’t have a daughter.”

“Your girlfriend is pretty, Willie.”

“Yes, dear. Roy’s wife is pretty.”

Mae responded with a three-year-old’s voice while looking at us. “I have Alzheimer’s disease.”

Willie took us on a tour of his home-plate shape swimming pool and garden, leaving Mae to continue her lounging. Willie Mays spoke about his wife and her family that thinks he should hire help for Mae’s care or place her in a home. Perhaps at some point, he said, but not now. “I can take care of her. I’m her closest relative, my goodness.” Smiling blushingly, he added: “I took a class on how to properly place a catheter. Been doing it for a year. She is my wife, not a patient in a facility looking over a beautiful view of the Pacific. A nurse comes by once a month to check on me and Mae. We are doing just great.”

On the way home, I remarked to Saundra, my wife, that we didn’t talk at all about baseball.

“I noticed,” she said. “He loves his wife. I want to keep in touch with them. I want to see them often. He is a good man, Roy.”

“The operative word is ‘man.’ The Man.”

After speaking to my grandson, Jamar, I made a call to an old dear friend and spoke for 30 minutes, then called Jamar back. “Do me a favor, little dude. Look up the World Series teams for 1971 and see if my name is in the Expos lineup. Do it now. I’ll wait.”

He came back to the phone with his laptop.

“I see your name in game six, Grandpa,” he excitedly informed.

“Any notes about how that game ended?”

“Wow! A walk-off home run by Ed Carroll scoring two runs breaking a World Series no hitter. The pitcher, Dave Shoupe, lost a one hitter.”

“Anything about a perfect game being spoiled by a Roy Williams?”

“No.”

“Hey, you guys,” I continued. “how would you like to meet a real baseball player for your report? I spoke to Willie Mays, and he said he would love to meet you knuckleheads. He still lives here in the Bay Area and Saturday, after your game, is a good time to visit. Bring that Sony digital camera I gave your mother. No cell phone pictures. I don’t do cell phone photos. I talk on phones.”

“Willie Mays, the hall of famer? You know him, Grandpa?!”

“He has been a friend for a long time.”

That Saturday, Jamar and Carlos stood in front of the passenger door of my truck waiting for me. They were standing side by side in their little league uniforms with mock turtleneck Under Armor under gear. Carlos was number two; Jamar was number four. Twenty-four. My number and Willie Mays’ retired-forever number. I paused to reflect on how quickly time passes, how old Willie Mays must be, how old I am, and how young these little guys are. Jamar looks like he will be a good pitcher and Carlos loves it behind the plate catching. Do they still call it the battery? The pitcher and catcher, I like those positions these days.

I told them of Mays batting .345 with 40 stolen bases in 1954, his first MVP award after spending two years in the Army in his early 20s. He hit 51 home runs in 1955. If he had not served in the Army, it is easy to think he may have around 100 more home runs to his total of 660. Hank Aaron didn’t serve. Mickey Mantle didn’t go. Mays is the only home-run leader and military veteran. A lot was made of Muhammed Ali missing three years of boxing at his prime but little if any concerns about Mays missing two years in his prime baseball years.

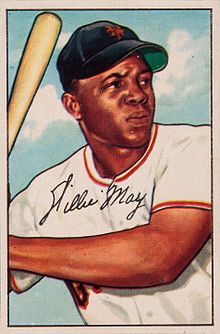

Before I started the truck, I gave Jamar a baseball card.

“This is your rookie card, Grandpa! Look, Carlos.”

“My only card. Your Grandpa is an educator. Willie Mays was the greatest all-around baseball player ever. The ‘G O A T.’ You guys keep an eye on Mike Trout with the Angels. He is the closest I’ve seen to Mays. It’s a game and they both enjoy playing.

“Hey, give me that card back. It’s very rare and worth little. I keep it in a safe place. You’ll get a card of your own one of these days. This one is mine. Just do your grip crushers. You’ll need strong forearms to hit four home runs in one game and have a batting average of .345 for the year. Which one of you guys is hitting over .345?”

These days Covid 19 has the healthy 89-year-old affable ballplayer, Willie Mays, isolated from people for the first time in his life. He has a small platoon of Covid-tested friends and relatives along with attentive health care providers all providing mental stimuli while locked down in his Atherton, California home.

Willie Mays has always been a news junkie and knows of Hank Aaron’s death and considers Aaron to have been a friend going back to the Negro leagues. Aaron was saddened that Mays did not take a leadership role in the civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King in the 1960s like Jim Brown, Rafer Johnson, and Muhammed Ali.

“I’m an entertainer. Not a politician. I make basket catches, steal bases, and hit baseballs. I do the very best I can doing what I do best.”