|

|

True PowerFictionPaul Lewellan

A fter giving birth to three testosterone-laden sons, Mother found a gender mate in me, her fourth and final child. I am petite with dark brown hair and tiny breasts. My brothers have red hair and thick necks. The shortest is 6’4”. They were football players and heavyweight wrestlers in high school. To them brute force was power. Obviously, they missed the complexity of power’s other manifestations.

The boys briefly respected my helpless babydom. Esau, my youngest brother, was eight when I was born. He would rather tie firecrackers to stray dogs than hold a baby sister. Absalom, the eldest, dismissed me as a “puking little slug” and acted out his torturous urges on neighborhood cats. My one scar from infancy was a bullet-shaped cigarette burn on my right thigh. Kane, my middle brother, gave me that, accidentally he said, when I was six months old and he was ten. Kane was babysitting while the Dad of the Month attended Mother’s new show at the Hot Spot. The beating Kane received impressed my brothers and made Mother a legend in Polk County social welfare circles. Mother wasn’t proud of it, but none of the boys tried to touch me again until I was much older and of more interest to them. By then I could take care of myself. My mother is eternally gorgeous, even late at night, in her old blue terry cloth bathrobe. In junior high, I would wait up for her on the weekends. After work Mother sat at the kitchen table with a box of Puffs and a jar of Noxema cream. Her Ready Stop mug steamed with coffee and a Virginia Slims burned in the ashtray as she removed her stage makeup. In the background I heard farm market reports from WHO in Des Moines. Spread before her were wrinkled dollar bills that men had given her, mostly ones and fives. Some nights she got home later. Then there were tens, twenties, and fifties. Even without makeup, she was golden. I wanted to be just like her, but she told me, “No. Miriam, you have to invent your own self.” That was difficult. Eventually, books provided role models. I read Alice Walker and Kate Chopin, Hurston, Gilman, Gordimer, Jewett, Plath, and Munro. But I also read Borges, Boll, Joyce, and DeLillo. When I entered high school I decided to be an English teacher. I learned from my guidance counselor that humanities professors are paid less than a Safeway produce manager. Paradoxical, isn’t it, that both Mother and I could become social outcasts because of our career choices? My brothers didn’t worry about being outcasts. East High School allowed them to graduate in exchange for time served on athletic teams and a promise they would leave the community after matriculation. Absalom joined the Marines and is on his third tour in Iraq. Kane moved to Kansas City where he drives six girls around in a limo he calls, “The Perpetual Money Machine.” Esau is serving twelve-to-fifteen at Fort Madison for armed robbery. “None of the boys got killed,” Mother told me. It was a poor standard for parenting, but then she did not have a good role model. Mother started stripping in her father’s club before she finished high school. The boys grew up in joints, never knowing their dads. “I’ve written down all the excuses why I wasn’t a better parent,” she said. “It’s three pages long. But they’re just damn excuses.” After I was born Mother became part owner of the Hot Spot (just off University Avenue near Peggy’s) and settled down in Des Moines. My father was going to marry her as soon as his divorce was final. He was a gynecologist who wrote speculative fiction. He got killed by a jealous husband on angel dust at the Free Clinic on Keo. “It ain’t Detroit,” my Mother would say, “but the East Side is tough.” The first day of school every year my teachers would read off the class rolls. When they came to “Boru,” I could see fear in their eyes. They knew my brothers. “Miriam Boru,” they’d call out. I’d demurely say, “Present.” The fear went away slowly. Esau once told me his grades improved after he’d set fire to his Composition teacher’s Ford Astro following a Friday night football game. The instructor was in the van at the time, engaged in heavy petting with a student teacher from the University of Northern Iowa. They escaped without injuries, but Mr. Howland’s trousers and his Astro were consumed in the blaze. Howland didn’t see who’d set the fire. On Monday, Esau handed in a term paper on burn therapies. It consisted of three plagiarized pages with no footnotes or quoted passages. “I think you’ll like my work,” Esau said to Howland. He received an “A” on the paper and ultimately fathered a child by the student teacher. I earned my grades. I did twice the work of everyone else, to assure myself I wasn’t getting good grades because of the family name. I scored in the 99th percentile on the Iowa Basic Skills and got 1590 on my SATs. I understood standardized tests. I also understood men. Mother’s occupation provided a laboratory for their observation. I remembered the time Mother collapsed on stage. A male nurse at a ringside table diagnosed her appendicitis. A CPA in the audience rushed her to the hospital in his Lexus. The bouncers took a collection before the last show to help pay the hospital bills. Mother told me dozens of stories about decent men, who one minute were hooting and trying to stuff bills in her g-string, and the next were treating her well. She was in control when she danced, but I didn’t want that kind of power. I wanted true power. I was tempted to dance just once. It was my senior year in high school. Mother wanted me to dance for my brother, Esau. He had just started serving time in Fort Madison. He blamed everyone but himself, claiming the crime was the result of childhood neglect, the failed school system, a lack of job skills, low self-concept, violence on TV, and the poor cash management practices of the Ready Stop chain of convenience stores. I sent him my copy of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotle writes, “It is absurd to make external circumstance responsible your action, and not your self.” Esau traded the book to another prisoner for a pack of Black Jack gum because he thought Aristotle “sucked.” Mother wrote him every Sunday night, after the last show. Monday was her day off, so she would write well past sunrise. She’d work at the kitchen table as I ate my Shredded Wheat before I set off for early-bird biology class. In six months she got three angry postcards from Esau, each one less angry. Just before Easter, he sent a letter seeking forgiveness and asking her to come visit. They exchanged letters every week after that, and she visited the third Monday of the month. By the time I visited in June, Esau had been transformed.

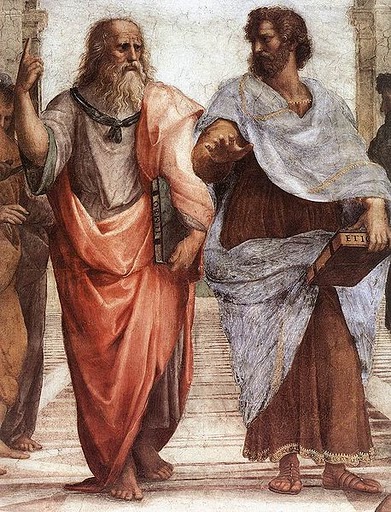

Detail of The School of Athens by Raffaello Sanzio, 1509, showing Plato (left) and Aristotle (right) T he first time Mother asked me to edit his letters it surprised me. “His English skills are for shit. His teachers never could get him to write, except that one student teacher. Now he wants to learn.” She’d read his letter, then make a photocopy. She’d keep the original, and I’d correct the copy, making suggestions on grammar and syntax. I corrected spelling, punctuation, and capitalization errors. I explained the rules he should follow.I hated it, and so did he. His eighteen-year-old sister was correcting his spelling as his teachers used to. Only I was tougher. And he couldn’t set fire to me. As I saw improvements, I encouraged him. Gradually, we became friends in a way we’d never been as brother and sister. As older brother he tried to be lord and master, dominator and abuser. When he let me teach him, I took charge. I highlighted sections in Strunk and White’s Elements of Style. I shared my theories of composition. Once he became submissive, we got along well. That’s why Mother asked me to dance. Mother convinced the warden that she was an entertainer on the Holiday Inn lounge circuit. She hoped to recruit girls from the club to give a show for Esau and the other prisoners. She asked me to join her. “No,” I said. “Even if you could convince the warden, which seems unlikely, these men don’t need more strippers.” She asked me, “What do they need? Books?” “Yes,” I said. “Mother, it’s time you read Fanon.” Franz Fanon argued that a person who possesses a language “consequently possesses the world expressed and implied by that language.” “Speak plain English,” she told me. “Language is power. If you can learn the master’s language, you can control the master’s world.” She looked puzzled. “If I can teach Esau to talk, read, and write like me, I can keep him from going back to prison.” That she understood. Mother borrowed my copy of Black Skin, Black Masks, and asked if there were Cliff’s Notes. When I shook my head, she shrugged her shoulders and disappeared into her bedroom. A day later she emerged with a plan. Mother borrowed her friend Sheila’s schoolteacher costume and went to see the warden. Mother has enormous powers of persuasion. Our first Great Books class had three pupils: Esau, Bob (his cellmate), and Tom (the prison librarian). I read excerpts from Frederick Douglass and led the discussion. “Douglass was taught to read by his slave owner’s wife. When the owner found out, he was furious,” I told our pupils. Then I read what Douglass’s master told his wife. ‘Learning would spoil the best nigger in the world. Now if you teach that nigger . . . how to read, there would be no keeping him.’” I put the book down. “That’s how Douglass discovered that literacy was his pathway from slavery to freedom.” I turned to Esau. “People let you slide by in school because by keeping you ignorant they could control you. I can teach the lessons they have kept from you. If you want me to.” Maybe my impassioned speech was the reason the class grew. But I have to admit, Mother looked stunning (tasteful, with just a little cleavage and an ample amount of leg). To recruit more men for class, all she had to do was walk from the prison gate to the library. Plus, she made me wear a skirt. By our third session there was standing room only. I acquired pen pals. I immediately threw out the letters that began, “Are you wet?” I couldn’t waste my time on such nonsense. My first year at Drake University, I corresponded with six inmates. Ultimately, they became my pupils in the Life Stories writing class I started at Fort Madison. I told prison officials that I could give the men a voice beyond their bars. Excerpts of their stories were eventually published in Esquire and in Reader’s Digest. Now I’m in grad school at Western Illinois University. I have almost completed my dissertation on composition instructional methods for confined pupils. Mother is taking classes at DMAC to get her Associate’s Degree. The Department of Corrections has hired me to coordinate a literacy program in Iowa prisons. As a grad student, I started great books discussion groups at a dozen men’s and women’s prisons and county jails. I enlisted campus sororities to develop similar seminars in other institutions. My program combined wholesome, educated, American women with basic instruction in reading, and discussions on great books. Jailers reported reduced violence and a greater demand for the classics. Passing rates on GED exams went up. Each new class begins with Frederick Douglass because Douglass knew that the master’s power did not come from the whip or the chains. It came from their capacity to read and write. That is the power I pass on to these men. Tonight I witnessed the end of an era. My mother danced her last dance at the Hot Spot. Four shows and a party after closing at the Knights of Columbus Hall. (Mother wants to devote more time to her studies) Customers from the past three decades came to pay their respects and shower her with dollar bills. As I watched her dance, I took notes. Not that I will ever dance like that. I promised Esau that I’d describe it to him. Every detail. There was nothing kinky in his request. No Oedipus and Jocasta. Esau wants to feel like he is part of a family. And he trusts the power of my words to take him there. He has found power, too. He’s writing his daughter, Emma, from prison. She’s the child he fathered with his student teacher. He’s finally found words to say to her. He takes the money he makes at the prison furniture store and buys her books on Amazon.com. He’s promised Emma that when he gets out he’ll go and read to her, though by then she’ll be in junior high school. And the child’s grandmother, my dear mother . . .? She has promised to teach Emma how to dance.

Paul Lewellan’s stories have appeared in South Dakota Review, Big Muddy, American Polymath, The Furnace, Iconoclast, and Opium Magazine. He is an Adjunct Professor of Speech Communication and Business Administration at Augustana College.

|