|

|

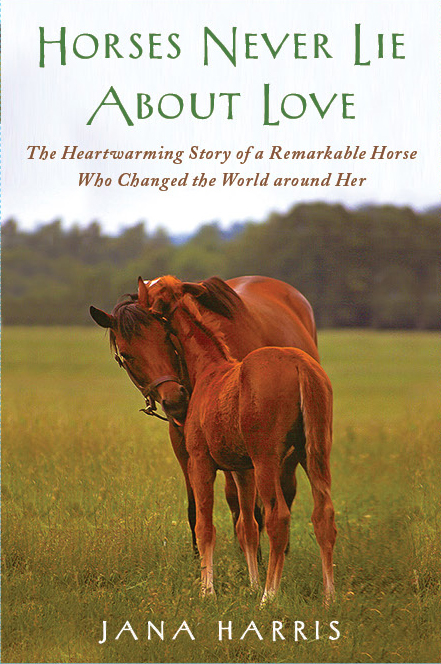

Horses Never Lie About LoveNonfictionJana Harris

I 've always had a hard time making decisions, especially decisions that involve spending money. I waffle, obsessively weighing the pros and cons, and eventually exhaust myself, in the end deciding nothing. But

on this particular spring day over two decades ago, at a horse ranch in

eastern Washington, I saw and knew exactly what I wanted.

It was May 1986. She was a deep red mare known as a blood bay,

standing about sixteen hands—sixty-four inches at the withers, where

the neck meets the back. Her arched neck flowed gently into her chest;

her pretty head had a white star and a narrow stripe dripping down her

face into two black nostrils. Something about the way she guarded her

foal, an ebony two-month-old, two-hundred-pound colt, spoke to me. The rest of the Rocking D’s herd of twenty thoroughbred mares and their foals stood placidly in the intense noon sun. The mares—bays and chestnuts mostly, one gray—raised little puffs of smoke whenever one of them stomped a heart-shaped hoof in the dust. All the foals looked black, though they had a few white hairs like frost around their eyes and furry ears. It was hard to tell; my husband and I couldn’t get closer to them than the corral fence. The mares had just been driven in from the range adjacent to the Rocking D, owned by Duke and Patsy, and weren’t used to being handled; foals are timid by nature. How had these mares survived the hard winters in the rugged Okanogan? They were thin-skinned and fine-boned, their legs as narrow as my forearm. As I was about to ask Patsy, who was standing next to me, the mares suddenly pricked their ears, all looking in the same direction at once. Behind an eight-foot-high barricade of telephone poles stacked next to a barn with a sagging roof, a gray stallion trumpeted, then furiously plowed the ground with a foreleg. Fine dust engulfed him, a Percheron from champion work-horse bloodlines. The massive crest on his neck foamed with sweat; his thick white tail cascaded to the ground, the ends caked with manure. I couldn’t see his expression because a white forelock covered his face, but his anger was palpable. Again my eye scanned his herd of mares. “That one,” I said to Patsy, pointing at the blood bay. “How old is she? Could we see her and her baby move around a little?” My words crackled in the clear dry air. At that moment, the mare and her baby sauntered away from the rest of the herd, where they were all corralled in a barbwire enclosure built below a granite outcropping mottled with sage and tarweed. The foal stopped, dropped his head, then crooked his neck to nurse, taking shelter from the high desert sun in his dam’s shadow. The mare’s tail whisked rhythmically across the foal’s sturdy back, sweeping it of flies. Not a hint of unhappiness in her expression; they were the perfect architecture of mare and foal. Mark and I had just driven our Honda Civic six hours east from the coast to the Rocking D. Leaving the black-green rain forest and gloomy skies of the Puget Sound, we’d traveled an open-in-fair-weather-only highway over a treacherous mountain pass. Emerging from the countless white peaks that disappeared into a fog of clouds, we plunged around hairpin turns into the desert side of the state, the change in altitude making my ears pop. I squinted in the light from a different sun, a disc the color of the already dry grass it overlooked as it hung in an endless sweep of amethyst sky. At the eastern foot of the Cascades, we turned north up a narrow valley heading for Duke and Patsy’s ranch, which—according to the directions I held in my hand—was located on land leased from an Indian reservation near the Canadian border. I saw almost no houses and could count the trees, spindly pines, on one hand. The only shadows were cast by angular moonscape rocks jutting out from the benchlands. The air tasted as dry as ash, the visibility so clear I could believe that we were seeing all the way to the Northwest Territory. I’d found Patsy’s ad for a herd dispersal in a flea-market newspaper: thoroughbred mares with half-draft foals, sold together or separate. The price: too good to be true—an incentive to drive halfway across the state into the middle of nowhere. I’d lived and breathed horses as a child and felt lucky when I’d been given one as a teenager. During college and graduate school, and the next decade of being a poet in Berkeley, I’d hardly seen a horse, my lust for them going dormant. Then, when Mark, my research-scientist husband, landed a university position, we found ourselves living in rural New Jersey’s horse country. We were so isolated that if I hadn’t taken up riding again, I don’t know how I would have found even one new friend. Now in our late thirties, we were back in the West with new teaching jobs, two riding horses, and some acreage we’d just purchased. Our new barn and covered riding arena (a costly affair but a necessity in Rainland) left only a tiny budget, if that, for breeding stock, should we decide to breed horses. Did I say decide? It had been my childhood dream. I had to pinch myself to make sure it was actually me living this life: horses, a farm, and now maybe a mare-in-foal with this year’s foal at her side. As our car approached a smudge of a town, I rechecked the directions that Patsy had given me and looked at the map. We drove past a row of clapboard houses with pole beans growing in the front yards. Neat stacks of cordwood reached to the top of the eaves of cottages on either side of the state highway. Across a swift narrow river, rows of apple trees frothing with white blooms stretched toward bald hills dotted with brown-and-white cattle. We drove slowly past a row of brick two-story storefronts built in the 1920s; a grain elevator rose up to the west. “When we come to a traffic light, turn right. Drive five miles, then start to look for a gravel road heading north,” I told Mark. He squirmed in the Civic’s utilitarian bucket seat, his long back fatigued by our journey. “There’s a traffic light?” he asked as he pulled up at a gas station. “According to Patsy, it’s the only one in the county.” “What’re the chances of getting a triple espresso macchiato?” he asked, looking out the car window and scratching his high forehead. He yawned, running his long fingers through his pale blond mop. “With an organic biscotti?” I joked. “I’ll get us a Coke. After we find the gravel road, it’s seven more miles.” Clearly, we were headed to the end of the galaxy. “Is there some way we could see her trot? And the foal?” I asked Patsy. It was a balmy day the temperature of bathwater; the sun warmed my back. A short, sturdy woman in her sixties with a lined face the same color as the brown hills, Patsy shaded her gray eyes with her hand, a thin gold band on her ring finger her only adornment. She turned to Duke, who had been standing laconically behind us, the heel of his cowboy boot dug into the dirt. He was lean, silver-haired, and stood six feet, taller if not for the stoop in his back. Stubble the color of the granite outcroppings shadowed his jaw. Removing the battered cowboy hat from his head, he wiped the sweat band with one hand, then spat in the direction of the wire fence, his marble eyes fused to the flinty dirt near where I stood. “What’ya say, Duke?” Patsy’s tone was motherly. “We could move the mares down to the creek pasture for a graze so Jinny—is that what you said your name was?—can see ’em run around. Those other buyers’ll be here soon—want a horse for their little granddaughter. Probably they’ll ask the same.” Duke pursed his lips into a line so thin it looked as if his mouth were a gash in his face. He nodded. “Yeah.” He smiled. “Let’s give ’em elbow room.” As he strode off to open the wire gate, I studied the letters of his name tooled into the back of his leather belt. When we’d first arrived, coming to the end of the gravel road and Duke and Patsy’s bunkerlike cinder-block house with a bearskin stretched across one side of it, I’d tried not to stare at Duke’s huge belt buckle, with its territorial-era silver nugget set in the center. It made me feel as if we’d driven to a different century. After I’d pried my gaze away from the shiny buckle, I’d taken in the panoramic view from the Rocking D’s ranch house, perched on a treeless bluff above an unpainted two-story barn, a stallion pen, and one corral. Below stretched the Valley at the Top of the World, its shoestring river fed by spring coulees and creeks rushing down from the white pinnacles that fenced the valley on the west. Before Washington became a state, this part of the country was known as the Chief Moses Reserve. As Duke opened the gate, the mares crowded together, eager to get away from the barn and into the open space. When they hurriedly moved away en masse, the stallion bugled after them, then threw himself against his telephone-pole barricade. The stockade shuddered; the mares broke into a trot. Plunging down the loose dirt of an incline, some began to canter as they fanned out, stopping at the edge of an almost dried-up freshet. They dropped their noses to the ground and began looking for grass. Some of the foals were huge, already the size of yearlings. A few had begun to turn from black to steel gray. The largest one limped. I searched for my mare and found her guarding her timid colt—in equine parlance, a young unneutered male horse is called a colt, a female horse under age five, a filly. “What’s her name?” I asked Patsy. She and Mark and I had followed the herd into the open space, pausing to watch them graze. “That’s True Colors. When we go back to the house, I’ll show you her papers.” As I walked toward the mare, she nuzzled her foal, and both quickly moved away. I took baby steps. I stopped, dropped my eyes, looked away. I walked backward toward her. Finally, I got close, but not quite near enough to touch her. I tried to memorize what she looked like: her only white leg marking was on her left hind, a French anklet with two onyx dots just above the hoof. When I crouched down, she turned her head away, studying me out of her peripheral vision. Her eyes were wide and gingerbread brown. As she regarded me, there was something about the way her eyes softened, the way their warm color feathered into the pink of the sclera where the upper and lower lid met—the color of a desert sunset. “What a handsome baby you have.” I spoke in a low, singsongy voice. Her foal had a perfect white star in the center of his forehead and reminded me of a breed of horse called an Irish hunter owned by several of my neighbors in New Jersey. True Colors sighed, then dropped her head and searched for grass. The colt eyed me with a combination of curiosity and alarm. I stared again at the mare’s white hind ankle, noticing an old scar that made an S from the bulb of her heel up to her fetlock joint. She had no other blemishes. The blood bay chewed a nub of grass, turned back, and considered me. She glanced at her baby, then again at me. I tried to read her expression. Doleful? “What are you trying to tell me?” I asked, inching my foot closer to her. Duke shouted something from up near the barn, where he’d remained. Patsy stood about fifty feet away, talking to Mark. She called to me, “Duke says, ‘Want ’em to move around a little?’” “Sure,” I said, but regretted it the next instant when I saw Duke lift a rifle and fire it into the air. The echo cracked back at us again and again. All of the mares and foals bolted as if shocked with electric prods, some getting separated and then calling to each other hysterically. Up at the barn, behind Duke, the stockade shook as the white wave of the stallion’s mane rose and fell above the top of the barricade. After a long few minutes, the herd sorted itself out as the dust they’d kicked up settled into the marsh. No horse seemed to have injured itself. What I had seen of True Colors’s trot and canter looked acceptable for dressage, the riding discipline I followed. Some of the mares began to mill around each other, anticipating a second blast. Another mare caught my eye: a black bay that resembled “my” mare, but not as refined. The black bay’s belly looked as if she had swallowed a Volkswagen. I pointed to her. “Ain’t foaled yet,” said Patsy. “True Colors’s sister,” she added. The dark bay may have taken an off stride or two when she spooked from the rifle shot. The gray mare with the refined Arab head had a chink in her back; she’d either cantered or walked but couldn’t trot. Walking toward the black bay, I noted that she wasn’t as tall as True Colors, maybe slightly over fifteen hands—one hand equals four inches. This mare watched me from the corner of her eye as she grazed, and I had no trouble walking up to her. Maybe not even fifteen hands, sixteen hands being the magic height of a dressage horse. But friendly. When I reached out and touched her shoulder, she flinched only slightly, as she would from a fly, then stepped away from me. Gentle, yes, but common looking. And maybe lame. After a few minutes, when no shot rang out, the more nervous mares stopped milling, and the herd calmed. The foals took a tug on an udder, then imitated their mothers, searching for new blades of spring grass. Some were so young that their necks weren’t long enough to reach the ground, and they pawed the creekbed in frustration. My mare positioned herself and her foal at the edge of the swarm, the same way she’d stood at the edge of the knot of mares when they’d been corralled up near the barn. “I want that one,” I whispered to Mark as we followed Patsy back to the house. He smiled approvingly. “She’s the best-looking. Skittish, though.”

class=MsoNormal> Our eyes met. I could tell that Mark was as stunned as I was by the otherworldliness of this place. Inside, Patsy pulled out mismatched chairs from a table—planks laid across two sawhorses and covered with a yellow vinyl cloth—that took up most of the kitchen in their two-room house. Mark, Patsy, and I sat down near the metal utility sink. Duke sat at the other end of the table near the trash burner, where there was only one chair. “Needs his elbow room,” Patsy said, dropping her voice. Even though the stove wasn’t lit, I could smell wood smoke leaking out of the knotty pine walls. “Oreo?” she asked, placing a chipped blue willow saucer of three cookies at our end of the table. She put on her reading glasses and fumbled with the accordion folds of a large manila file. “True Colors’s papers,” she said. Duke jabbed a filterless cigarette between his lips but didn’t light it. I studied the horse’s pedigree: Round Table was her dam’s grandsire—one of the biggest stakes winners in history. She had very decent bloodlines. Patsy turned to Mark. “Don’t ya got nothin’ to say?” she asked. “You ain’t said more than two words since you got here. Don’t let us hens dominate the conversation.” She had a high, nervous laugh. “Coffee?” she asked, jumping up and lighting one of the burners of a black restaurant-sized stove. “Don’t I got a lotta pep for an old broad?” Mark’s back straightened, and his eyes lit up. “I’d love some,” he said. Patsy unscrewed a jar of instant Nescafé with a strong meaty hand, and pushed the saucer of Oreos in front of Mark. I continued to study True Colors’s papers, turning them over to look at the description of the mare’s white markings: face, left hind, one cowlick on her neck. “She’s eight years old,” I commented. “How long have you owned her?” “Condensed milk?” Patsy asked Mark. The coffee tasted strong and bitter. Duke lipped his unlit cigarette. A white cafeteria mug of hot water steamed in front of him. “Bought a load of thoroughbred mares from an outfit in Yakima. Three-, five-, ’n’ seven-year-olds,” Duke said distractedly. Patsy jumped in. “Some was in foal. Some we thought we’d race at the Playfair track in Spokane.” “So she’s been broken to ride for the racetrack?” I asked. Patsy didn’t answer. “She was in foal,” she said after taking several sips of coffee. “How’d she get that scar on her hind leg?” I asked. Duke’s marble eyes widened, and he was suddenly animated. “Jumped outta the truck when she got here,” he said excitedly. He took the unlit cigarette from his mouth and made arcing motions with his arm, tracing the mare’s trajectory, his hand almost hitting the black stovepipe of the wood-burning furnace. “We’d just put down the loadin’ ramp. I opened the tailgate and the first mare—they was packed tight—” “Less likely to get hurt that way,” put in Patsy. “Just as the filly closest to the loadin’ ramp started to walk down it, some harebrained mare panicked. True Colors lit over the side, snagged her leg on something, I guess.” I took a hard swallow of coffee. “Did the vet have to take many stitches?” I asked. “Couldn’t catch her,” said Patsy, adjusting the collar of her faded pink flowered cowboy shirt. Pearlized snaps ran down the front of it. She pulled the top snap open. “So we let her range. It’s what we did with all the mares when our racin’ program fell through. Here’s a picture of her first foal.” To Mark, she passed a photograph of a sturdy chestnut as bright as copper teakettle. “That there one she’s got on her now is her second foal. It was a coupla years after we got the racing mares that we bought our draft-horse stud, Knight of Knights. Your mare had both them foals on the range.” “You seen our stallion down there in the bullpen?” Duke asked Mark. Mark nodded. No one could forget the one-ton gray pawing the ground and throwing himself against the stockade wall. “Don’t worry.” Duke chuckled. “He can’t get outta there.” His small eyes glistened under the heavy overhang of his brow. “Percherons are natural jumpers,” he added wryly. “You the people lookin’ for a jumper?” Patsy asked. “Dressage,” said Mark. “Kind of like ballet on horseback.” “Oh, so you can talk.” Patsy laughed. “You ride, too?” “A little,” said Mark. “Still learning.” “What about your kids? They ride?” Patsy wanted to know. “I had high hopes of my kids cottoning to ranch work.” Her voice trailed off. “No kids,” said Mark. Patsy looked stricken. “You newlyweds? How long you been married?” Mark didn’t reply. “Almost nine years,” I said after a silence. I braced myself. Patsy’s mouth puckered as if she’d bitten into a sour apple. “Poor Mark.” She spat out the words one at a time with a breath in between. She looked at me judgmentally but added, “Well, I don’t blame a body these days for not wanting to adopt.” Mark raised his shaggy Harpo Marx eyebrows. I felt a long way from my world. “I think I’d like to buy True Colors and her foal,” I said. “But I want a vet to check and make sure she’s in foal for next year.” Patsy smiled while biting her lip. I wondered why. A stunning thoroughbred mare that could foal on her own without complications and raise her baby on the range, showing it where to step, and how not to put its hoof in a hole—what a piece of luck. “Vets around here are pretty busy vaccinating cows right now,” Duke drawled. “She ran with the stallion until two weeks ago, and I ain’t seen no sign of her cycling,” Patsy added. “I’m sure he caught her on her foal heat.” “What do you do in an emergency?” I asked. Patsy looked at Duke and shrugged. “Turn ’em back to God,” she said. Nobody spoke. I took an Oreo from the plate and bit into it. “We’ll keep a close eye on her,” Patsy offered. “She shows any signs, we’ll put her back with him.” I scraped the white sugary filling off the cookie with my teeth. A thoroughbred mare that could pasture-breed was hard to come by. Thoroughbreds were bred to do one thing: run fast at an immature age. Most of the sense had been bred out of them. Their hooves were notoriously shelly, their long-term stamina questionable. But this mare seemed to defy those odds. Her feet had good-quality black horn, not a crack or a chip, though the ground was hard and rocky. When I’d seen her move around in the dry creek pasture, she’d trotted sound, no evidence of stone bruises. Given her unprotected, almost feral life, I was surprised that True Colors had only one scar. Still, her distrust of people was a consideration. “Here’s that other mare’s papers,” said Patsy. “True Colors’s sister.”

class=MsoNormal> I glanced at the Jockey Club insignia. "This mare’s twelve,” I said. I didn’t want a mare older than ten. All the same, I looked over the documentation carefully. “More coffee?” Patsy asked Mark. He shook his head. Duke banged his mug on the table. Patsy jumped up and poured him seconds of hot water. “When’s she due to foal?” I asked. “True Colors’s sister? Next couple of weeks. She’s got a bag on her but no wax; you know, the clear stuff that comes out of her nipples before her milk starts to flow. ’Course, a mare can foal without giving any signs.” The crunching noise of tires rolling over gravel wafted through the kitchen window. I looked outside as a battered white pickup with an oversize camper lumbered up the road toward the house. When the driver braked, the camper lurched dangerously from side to side. A long trail of dust and exhaust slowly drifted toward the stallion pen. "Them’s the buyers from Wenatchee I was telling you about,” said Patsy, quickly shelving the Oreos. The young girl, Ronella, passed her pink plastic horse to her grandmother and then began to make rapid jerking motions with her arms. “Horsey, horsey,” she called in the direction of the Rocking D herd. She pummeled the air. Ronella wore pink cowboy boots, pink shorts, and a pink-striped T-shirt that didn’t quite cover her poochy stomach. Mark and I and the new buyers followed Patsy down to the creek for another look at the mares and foals. Duke lagged behind. “She’s almost seven, but she’s still got a touch of the terrible twos,” said Ronella’s grandmother, a rosy-faced woman with sausage arms. She wore a ruffled Hawaiian-print shirt that billowed over the waist of her size double-X jeans. Gammy had tiny feet and shuffled along in a pair of white tennis shoes, taking baby steps. “We had to park her in the camper when we stopped at the casino,” Ronella’s grandfather told Patsy, his voice put upon. Butch wore regulation Wrangler jeans that looked as if they’d been washed and dried to his coat-hanger shape. His tooled-leather belt had a dinner-plate-sized silver belt buckle, and his Western shirt was made out of the same Hawaiian print as Gammy’s blouse. “She never naps long enough,” said Gammy. “Thank Jesus for NyQuil cocktails.” “Jinny here says she’s buyin’ that mare and foal,” Patsy said, pointing to True Colors and her baby. I smiled. Already I was proud of my pretty girl. Butch gazed politely at True Colors. Gammy clicked her tongue. “Which horsey would you like?” Patsy asked Ronella. I scanned the herd for the small dark bay, True Colors’s sister. She dozed in the sun, her ears lolling. Her head was long but not unattractive. And no chrome—not one white marking on her. Ronella pointed to True Colors’s foal. “Mine,” she said. “No, ’Nella,” said Gammy. “That one belongs to this lady here.” Ronella’s face broke into a thousand pieces. “Mine!” she wailed, beating her fists against her grandmother. “Mine, mine, mine.” The herd looked uneasy. Most of the mares stopped eating, jerking their heads in our direction. True Colors pushed her baby to the other side of the herd. As my foal lowered his head and crooked his neck to nurse, True Colors gazed anxiously back at us, her head over the foal’s back as if to shield him. Her ears were shaped like gilded lilies. Her perfect conformation and her white anklet with the two onyx jewels reminded me of the horse in an 18th-century painting at the British National Gallery: Bay Horse and White Dog by George Stubbs. Only the background was different. Instead of the English countryside, here there was a desert landscape: one cottonwood beside a bend in the creek. I called to her, “Don’t be afraid, Mom. We won’t hurt you.” Ronella dropped to the ground, kicking and beating the scant grass. “Mine!” she screamed inconsolably. Her face reddened; tiny pebbles stuck to her wet mouth and pointy little chin. “Let’s find you another pony, sister.” Butch yanked her to her feet by one arm. “Don’t forget about Trigger.” Gammy waved the plastic horse. "That one,” said Ronella. Butch held her to his chest as they strode off after the largest foal in the herd, a steely gray colt that limped badly on one hind leg. Mark, Patsy, Duke, Gammy, and I watched as the pair was able to walk up alongside him. “How big will he git?” Gammy asked Patsy. “Well, there’s his daddy up there.” Patsy pointed up the incline to the stockade next to the barn. “Could get as tall as Knight, but more refined, like these mares here.” “Why’s he limping?” I asked. “Sore foot,” answered Patsy without hesitation. “The young ones got soft hooves. Stones, thorns—maybe he caught it in a groundhog hole. He’ll come right.” I wondered how she could possibly know. “And when could she ride him?” asked Gammy. Mark and I exchanged glances. Did Ronella even know how to ride? “Probably by the time he’s three,” said Patsy. “These crosses grow till they’re five but have most of their height by the time they’re three. If I was to guess, I’d say he’d grow to be sixteen, seventeen hands. Big, yes, but they got good temperaments, most of ’em. And ya know how horses love children.” Mark and I read each other’s thoughts. Tiny child with possible developmental problems, paired with a giant unschooled horse. What could her grandparents be thinking? Butch had gotten close enough to pet the large gray colt. “Oh, don’t that man have a way with broncs,” piped Gammy. She shook her head in praise and adoration and wonder. Patsy agreed. “Jinny here couldn’t get closer than a few feet to the ones she’s buying,” she said, motioning to me. As Butch tried to lift Ronella onto the two-month-old colt’s back, Ronella shrieked joyously. I opened my mouth to object but held my breath and grabbed hold of Mark’s arm. The foal’s fear overruled his pain, and he leaped sideways, alerting the mares. The entire herd bolted, followed by a tremendous pounding of hooves. Flying dirt and creek stones hailed down around us. The herd moved off, funneling into the creekbed and then running along it like a road. In seconds they’d galloped up the freshet into a canyon and out of sight. I took a long breath as my heart slammed repeatedly in my chest. “Horsey, horsey, come back,” Ronella cried, and her fists pummeled the air. “It’s okay, ’Nella,” called Gammy. “Don’t cry, cookie. Grampy’ll give you a piggyback. Butch, put ’Nella up on your shoulders. That’ll stop her crying.” Patsy, Gammy, Mark, and I walked back to the house. Ronella, her grandfather, and Duke started to hike up the canyon, where the herd had corralled itself in a blind coulee at the foot of a perpendicular granite ridge. “I hope my new horse and her foal didn’t get hurt.” Though I tried to conceal my extreme annoyance, I wanted Patsy to know I felt rattled. Appalled, actually. I could tell by the way Mark grabbed my hand that he also felt shaken, as if we’d just witnessed an almost fatal car accident. “You’re a nervous one,” Patsy told me, but not unkindly. “Got yourself a city girl, don’t ya?” She winked at Mark. Up at the house, Gammy excused herself and headed for her camper to take a nap. “Been a while since I had kids underfoot.” She pressed her index fingers to her temples. Inside the ranch house, I wrote Patsy a check for a mare in foal and a two-month-old colt. “So,” I said, “no way to get True Colors preg checked?” I was buying a mare in foal and wanted to make sure that was the state she was in. There was no way I could bring her all the way back here to be rebred. Besides, Duke and Patsy were selling out, moving to town—the one with the only traffic light in the county—because, Patsy said, “winter’s gettin’ to be too hard at the ranch.” And because of Duke’s heart condition. “Had it since he was a child,” she added, “but startin’ to affect his circulation.” “I’ll watch her for signs of coming in heat,” assured Patsy. As if on cue, the stallion bugled, then kicked the barricade. His white mane was so thick that it parted in the middle, falling on both sides of his neck. Even without grooming, his gray dapples gleamed in the relentless sun. He had no shade and, as near as I could tell, no water. “Price of purchase includes delivery,” Patsy went on. “Middle of August would be best for us,” Mark replied. I could see him mentally calculating all the work he had to do. We’d contracted to build the shell of a ten-stall barn and arena. It fell to Mark to finish the interior: build the stalls, hay loft, feed room, tack room, and grooming stall. We had two pastures for our two riding horses, but now we’d need to build paddocks. Suddenly, it felt as if we were in over our heads. “Sure you don’t wanna buy True Colors’s sister, too?” Patsy asked. She handed me True Colors’s registration papers and a bill of sale. “Then your foal would have a friend to grow up with,” she added. “Easier for 'em that way.” It wasn’t too late to change my mind. I could buy the other mare instead; she was older than what I wanted and not anywhere near as elegant and maybe lame (what thoroughbred wouldn’t be sore running barefoot on such rocky soil?), but she was more tolerant of humans. We were going to sell the foal next spring and use the money to buy hay. I exchanged looks with Mark. His eyes appeared silver in the indoor light. I took a deep breath and let out a long, slow exhale. “If the other mare has a healthy filly,” I said, “I’ll buy the baby.” “Deal,” said Patsy, immediately registering my check in her black account book. “Three horses delivered to your farm in August. A mare and two weaned babies.” Done, I thought. I suddenly knew that no matter what happened, there was one thing that I would never regret: saving this exquisite mare from whatever fate fell to her if I walked away without her. At the time, I had no idea how difficult it could be to wean a foal, so I didn’t thank Patsy for all her efforts in what I saw as purely a business venture. I probably should have. Though I’d ridden green horses and rogue horses, I’d never raised a foal. I’d never broken a young horse. I’d never foaled out a mare. I’d never euthanized a horse. I had no idea that breaking an older horse was different from breaking a youngster. I’ve often wondered: What if, at this moment, I’d been able to look down the long road that awaited True Colors, her foal, and me and taken back my check, forgotten that mare, her foal, and the little unborn one? What if I’d gotten into my car and on the road to home and never looked back? What would my life have been like? Mark navigated our car south along the miles-long undulating gravel drive. The setting sun stained the sky the rust-red of Japanese maples. The color reminded me of the corner of True Colors’s downcast eye as she had turned her head to her foal and then glanced back at me, her expression softening, entreating me not to harm her baby. Without ever touching her, I knew that this was a mare with a good heart. As we drove, the country felt vast and treeless and empty: a narrow river valley cross-cut by darkening coulees and striated benchland. How had those horses survived on their own in this desolate range? The shadows lengthened. Neither of us spoke. Only a few hours ago, we’d been dabblers, equestrian enthusiasts who owned two pleasure horses. Now we owned five, possibly six—three or four more horses for the price of one, an instant farm family. All we had to do was wait. Mark flipped on the car’s headlights. “What are you thinking about?” I asked. “About making hay from the grass in the back pasture of our new property,” he said. He wondered how much used balers cost, and mowers, and manure spreaders. As our car began to climb the steep grade up the eastern side of the Cascades, heading back to the Puget Sound area, I closed my eyes and dozed, thinking of my new broodmare. Little did I dream that I would own this horse for a generation, well into the next century, and invest more of myself in her than any other horse: this feral mare, the soon-to-be cornerstone of my farm and life; this albatross, this anchor—this grand passion. Excerpted from Horses Never Lie About Love by Jana Harris. Copyright 2011 by Jana Harris. Published by Free Press.

Jana Harris is an award-winning poet, short story writer, essayist, and novelist. She is the founder of Switched-on Gutenberg, one of the first on-line poetry journals. Her first novel Alaska was a Book-of-the-Month Club alternate selection. She just released her memoir, Horses Never Lie About Love. She teaches for the University of Washington and The Writer's Workshop.

|