|

|

Climbing the Dragon’s BackNonfictionNick O’Connell

Mountains in the Wind River Range. Photo courtesy of G. Thomas. T here are no handholds!" Tom stared at the

traverse in front of him. "There are no handholds!"

My climbing partner was poised behind the crux move on the East Ridge of Wolf's Head in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming. A 20-foot horizontal crack separated him from safe ground. All he had to do was shuffle his feet across the inch-wide shelf and the summit would be ours. But the rock above the crack was smooth; there was nothing to pull or grip or grab. The rock only could serve for balance as he moved his feet. If Tom were on a playground, he could have easily performed the maneuver. But he was clinging to the side of a granite face with 1,000 feet of air underneath him. He was tied to the climbing rope and I had him on a good belay at the other end of the crack, but it was hard for him to ignore the exposure.

"Use your hands to balance," I yelled. "Keep your butt out. Don't hug the rock."

Tom looked as if he not only wanted to hug the rock, but plaster it with kisses. He took a step and then retreated to the safety of a ledge. It was not going to get any easier for him. The longer he looked at the traverse, the more difficult it would be to cross it.

"I've got a good stance," I shouted. "Don't worry. Go for it."

I tried to sound calm, but I was very concerned. Tom had little rock climbing experience. The move was not technically difficult, but it was psychologically terrifying. And if he slipped, he'd take a scraper: a long, skin-abrading fall that would send him in a wild pendulum across the face. Not only would this prove painful, it also would make it extremely difficult for me to winch him back up. I tugged at the four pieces of gear in my belay anchor. They seemed solid, but you never know.

"Okay, Nick," Tom said. "I'm going to try it."

"Good," I said. "I've got you."

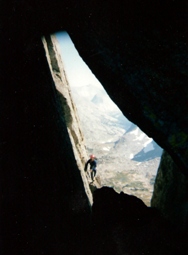

Tom Remmers approaches the crux section on the East Ridge of Wolf's Head Peak in the Wind River Range. Photo by Nick O'Connell W hen I organized our trip to the Wind River Range, I never

expected that Tom would attempt Wolf's Head. Alex Hall and I, both experienced

climbers, planned to do the technical routes. Alex is a short, muscular,

impressively accomplished alpinist who's knocked off everything from the

Salathé Wall in Yosemite to peaks in Patagonia. I shimmied up the bedroom

dresser as a kid and graduated to Himalayan peaks as an adult. Alex and I have

done some great routes together, including the classic North Ridge of Mount

Stuart in the Washington Cascades. On this trip we hoped to do several more.

The plan was for us to go rock climbing while our friend Tom Remmers, a veteran hiker and novice climber, and Alex's wife, Leslie, a former member of the U.S. Cross-Country Ski Team, went hiking. The Winds offer not only remarkable rock climbing, but also spectacular alpine rambling over well-graded trails. We would walk 10 miles into base camp at Lonesome Lake and then pursue our separate activities.

That was the plan.

At the lake, we camped in a boulder-strewn meadow smack dab in the middle of the Cirque of the Towers, the inner sanctum of the one of the most rugged and remote ranges in the American West. We were surrounded by immense granite towers like Wolf's Head and Pingora, all covered with long, steep climbing routes. In a place like this, Tom and Leslie likely had a hard time not thinking about climbing.

After a dinner of pasta and a bottle of Oregon Pinot Noir, Tom brought out a fifth of Oban single malt scotch and several South American dictator-sized cigars. Before long, the talk turned to the possibility of Tom and Leslie doing a route.

One thing led to another, and the next day we woke at 6 a.m. to attempt the South Face of Pingora, a six pitch, 5.6 route on glittering orange granite. Trained as a chemical engineer, Tom is a wiry, irrepressible character with brown hair, an untrimmed beard, and dark eyes that gleam with mad scientist intensity when he gets excited. They were in full gleam as we got on the route.

Tom and I went first and Alex and Leslie followed. I led the pitches, putting protection into the rock and belaying Tom up behind me. On previous rock climbs, he’d seemed shaky and uncertain. Today he moved with confidence. Halfway up the route, a thunderstorm hurled jagged lightning bolts at nearby peaks, but Tom kept his composure. When we reached the top, he and Leslie whooped in celebration; their joy was contagious.

On the way back to camp, Tom talked about doing Wolf's Head.

"It would be great," he said. "It's only 5.6."

"Yeah, but it's 20 pitches long," I said. "Plus it's a ridge traverse. It would be a lot harder to bail off." If a storm moved in, we couldn't rappel back down the route. We'd need the skill, stamina and determination to complete the climb. I wondered about Tom's ability to do this.

"Let's see how things go," I said. The plan was for Alex and me to do the Northeast Face of Pingora, a 12-pitch, 5.9 route for experienced climbers only. Tom and Leslie would do some hiking and exploring. After that we'd think about doing another climbing route.

The next day Alex and I knocked off the Northeast Face of Pingora, getting some hard climbing out of our system. That night we sat around the campfire and regaled Tom and Leslie with how we got off route and ascended 5.10 pitches. This only whetted Tom's appetite for climbing. As we talked and sipped scotch, Alex broke in.

"Me and Leslie want to do Wolf's Head," Alex said. "I don't think it will be too bad."

Alex is a veteran climber and I respect his opinion. But I hadn’t counted on his wanting to do the climb with Leslie. She was very fit, but she had done little rock climbing. If she came with us on Wolf's Head, Tom would want to come, too.

I could see myself getting outvoted. I could've backed out, but I wanted to do the route. Though I prefer to climb with experienced partners on challenging routes like Wolf's Head, I occasionally pair up with a novice. But I'm always a bit on edge.

"Okay," I said. "I guess it's Wolf's Head."

"Yes!" Tom said.

Nick, Leslie and Tom are all smiles at the summit. Photo by Alex Hall. T he weather was cold and clear at 6 a.m. We quickly packed

our gear. Tom grabbed the rope while I carried the heavier pack filled with

lunches, water, and climbing gear. I didn’t want him tiring himself out on the

approach.

After hiking up to the base of the route, we stashed our boots and packs behind a large boulder and put on our rock shoes. We managed to find the key passage through the cliff band and ascended low-angle slabs to a flat spot on the ridge crest. The view was wild and alpine, steep granite peaks soaring around us. The East Ridge of Wolf’s Head looked as dangerous and forbidding as the back of a dragon.

We uncoiled the climbing ropes and sorted the hardware--chocks, Camalots, slings, carabiners. Alex and Leslie went first while Tom and I prepared our gear. I stepped into my climbing harness and tied into the rope. Tom did the same. I checked to see that his knot was properly tied.

"Just want to make sure you're doing it right," I said.

"That's okay, Nick," he said. "I want to be safe."

"That makes two of us."

At 8 a.m., Leslie belayed Alex up the first pitch. He carefully worked his way across the appallingly narrow ridge--18 inches wide at this point--with a sheer drop on either side. While this section was not difficult in terms of technique, the exposure made it thrilling.

After Alex and Leslie finished the pitch, I got ready to go.

"Belay on?" I asked Tom.

"On belay," he said.

I eased my way onto the ridge, keeping my hands on the rock for balance as I moved my feet up. I avoided looking down and tried to focus only on the rock in front of me. The passage was easy as long as you kept your cool. I moved up to a stance below Alex and Leslie.

"That was wild," I said.

"Sure was," Leslie said. With her wispy red hair, flushed cheeks, and winning smile, Leslie looked like a poster child for outdoor adventure.

I set up my belay carefully. I put in four pieces, probably more than necessary. Tom weighed 150 pounds but a fall could generate a lot of force. I wanted to be able to hold a freight car.

"Belay on," I said, tightening the rope in my belay device.

"Climbing," he said. His legs wobbled as he moved across the narrow ridge, but he kept going. As the ridge widened, he scampered up it.

"Wow!" Tom grinned. "That was great."

I smiled, glad to hear the excitement in his voice. Pushing yourself on a climb like this can force you to come into your own as a climber, or it can reduce you to a quivering, twitching, nervous wreck.

Tom wasn't quivering yet. But this was just the first of many tricky sections of the route, where a slip could result in a 50-foot fall. Every time I placed a piece for protection I wondered, "If Tom falls, will this hold?"

Fortunately, the rock afforded plenty of hand and footholds as well as cracks and slots. The gray granite was speckled with green and orange lichens, decorated with whorls of minerals and full of surprises--a pocket here, a crack there, a knob or chicken head over there. The climbing was varied and spectacular. The views of steep granite towers and snowfields went on for miles.

The route wove between towers, up chimneys, and out across ledges. Every lead presented a new challenge. There were traverses, laybacks, friction moves--none of them technically difficult, but all made scary by the exposure. Tom seemed alternately intimidated and exhilarated by the climbing. But if he moved shakily, he always kept going.

By mid afternoon, we neared the summit. We passed through a keyhole and emerged at the foot of a traverse on the north face. This was the crux.

I caught up with Leslie. She was belaying Alex, who was taking a long time--not a good sign.

Then it was her turn.

"Oh God," Leslie said, looking at the sheer cliff in front of her.

"Good luck.”

"Thanks," she said, "I'll need it." She moved carefully around the corner and out onto the ledge. Tom and I huddled at the stance. We drank some water and ate a few squares of chocolate. We'd been going non-stop all day, running on adrenaline. Now we were suddenly hungry and tired and wanted to rest. But the summit was near and storm clouds gathered over peaks in the distance. No time to slack off.

Leslie swore loudly as she crossed the crack. Then her profanity became muffled. I got ready to go. I checked the belay anchors. They seemed solid. I made sure that Tom was holding the rope correctly through his belay device.

"Climbing," I said.

"Climb on," he said.

My fingers tingled with anticipation. I climbed around the corner and saw that the ramp continued on the other side and stopped at the foot of a sheer face. A 20-foot 1- to 2-inch wide horizontal shelf ran across it. I placed a piece next to the shelf and then stepped out onto it. There were no hand-holds. There was nothing other than my feet and balance to keep me from falling off the wall. I shuffled along the shelf and worked my hands along the face.

Midway, I stopped at a fixed piton. I worked a carabiner and sling out of my rack and bent down to clip them into the piton. A gust of wind made me lose my balance—a jolt of fear shot through me. I recovered and tried again. Finally, I got the gate of the carabiner inside the piton. My feet were killing me. I took another carabiner from my rack and clipped it into the sling and then into the climbing rope. The click it made as it snapped shut sounded beautiful to me. If I slipped, the fall would be short.

I worked my way up to a standing position. The ledge narrowed. I moved my hands over the rock, desperate for a bulge or crack or depression. Nothing.

I dusted my fingers with white gymnastic chalk to dry them, took a breath and set off. I moved quickly, using the wall for balance. Not quickly enough though. My toes were screaming at me. They had been taking my weight of 170 pounds for too long. I gritted my teeth and kept going, resisting the urge to lunge at the vertical crack five feet away. I traversed along until my toes could no longer stand it. I jumped toward the crack and sunk my fists into it.

Breathing deeply, I climbed the vertical crack to a good stance. Just in case, I put in four pieces of protection. I wanted a bomber placement here. Tom's fall would generate a lot of force on a traverse like this.

"Belay off." I called to him.

"Okay," he said.

Now it was his turn. Tom had been on a roll all day, but this stretch clearly terrified him. He made it as far as the traverse and then retreated. His legs shook. His arms trembled. The gleam had left his eyes.

"It's just twenty feet,” I said. “You can do it."

His eyes turned dark, serious, intent. "Okay, I'm going to try it," he said hoarsely. He stepped onto the crack. He moved unsteadily but kept going. His herky, jerky movements would win no style points, but they were effective. One foot. Two feet. Three feet. He shuffled along until he reached the piton, bent down and unclipped the carabiner from it. He clipped the carabiner into his sling and continued. His hands frantically searched for holds, while his feet stayed in the crack. An updraft nearly knocked him over.

My hands tensed as I pulled the rope through the belay device. I worked the rope carefully, anticipating the force of his fall. I kept the slack out of it, but avoid pulling it taut. I didn’t want to jerk him off balance.

He regained his footing and kept moving. Twelve feet. Thirteen. Fourteen. When he was within five feet of the vertical crack, he jumped for it. I clamped down on the belay device. He shoved his hands into the crack and clawed his way up it, trying to keep from pumping out. When he reached me, he gave me a big bear hug. The mad scientist gleam returned to his eyes.

"Yes!" he said.

"You did it!" I said.

He bent over and hyperventilated. "I can see why you're so calm," he said between breaths. "You have to be if you're doing this."

"Yes," I said, my palms sweating. "Climbing keeps me calm."

After he caught his breath, we kept going. A few minutes later, we joined Alex and Leslie at the top. The view was fantastic, granite peaks in all directions--Shark’s Nose, Watchtower, Warbonnet--the jagged spine of the Continental Divide stretching into the distance. We ate, drank and snapped photos, but saved the celebration for camp: it was 3 p.m. and clouds had massed in the west. The descent was long and complicated, but Tom bounded down it like a jackrabbit. By the time we reached our packs, my rock shoes had blistered my feet. I wasn’t looking forward to the hike back to camp.

We changed shoes, sorted our gear and got ready to go. I reached for the pack, but Tom grabbed it.

"I can carry the pack," he said. "No problem."

|