You're All WankersNonfictionJeff Smoot

K erwin Klein was back in Joshua Tree and giving us a tour of campground boulder problems one afternoon when a group of climbers doing a bouldering circuit swarmed into our camp. This group was more mature than the degenerates we were accustomed to—quieter, better dressed, the kind of climbers who might have driven out from Santa Monica on Friday night, stayed at the

Joshua Tree Inn, and had dinner and drinks at Arturo’s after each day’s climbing. They quickly dispatched all the problems we had just struggled to climb, gliding up holds we had barely managed to hang on to, some wearing only running shoes, which only added to the insult. They even climbed the face of the huge boulder behind camp, a twenty-foot-high nearly blank line that looked to be at least 5.12. We had eyed that problem for weeks and had never dared try it. They scampered up it without any apparent hesitation.

Most of the group had finished their circuit and moved on, except two climbers who were bringing up the rear. They were both tall, brawny hulks, built more like NFL linebackers than climbers, with nearly identical heads of short, curly hair. Showing off their overdeveloped physiques in tank tops and too-short running shorts, they seemed too large, too muscle-bound, to have finessed their way up these problems.

“Who are those guys?” I asked Kerwin.

“That’s Largo,” Kerwin said, “and the other one’s Gaines.”

John Long, better known as “Largo,” and his current sidekick, Bob Gaines, had invaded our campsite. Long, the quintessential Stonemaster, he of the first one-day ascent of the Nose, the first free ascent of Astroman, and author of some of the most outrageous climbing stories ever published, was as mythical a character as John Bachar or John Gill. He had probably climbed every route at Joshua Tree a hundred times, most of them solo and blindfolded with one hand tied behind his back, or so one might have believed from reading his stories. Long had a reputation as a spinner of fantastic yarns, prone to hyperbole. There was certainly a grain of truth in all of Long’s stories, you could tell, but you could not be sure where the grain ended and the chaff began. Truth be damned, his stories were gripping and usually hilarious. As for Gaines, he was, I was told, also a former college football player turned climber, hence the linebacker build.

Todd subjected Largo to the Skinner Inquisition, grilling him for information about particular routes all over the place: JT, Yosemite, Granite Mountain, Tahquitz Rock. The object of Todd’s most grueling interrogation was Hades, a route Largo had just climbed on the south face of Suicide Rock, a couple of hours’ drive south from Joshua Tree. He’d rated it 5.12+, like so many of the newest hard routes. No one dared suggest a grade of 5.13, afraid Jerry Moffatt would come over, flash it, and downgrade it to 5.12c, much to our utter humiliation.

Largo described his ascent of Hades like a high school quarterback on homecoming night recounting his game-winning pass. We hung on everything he said. On the first pitch he made desperately thin 5.12 face moves up a nearly featureless wall to reach anchors halfway up the south face. Above the anchors there was an expanding flake that was so precariously perched it threatened to peel off under body weight. Long had to stand on it, all 220 pounds of him, risking death with each move—not only his death, but the death of his belayer hanging helplessly twenty feet below him. From there, the route went up a slab that was even more featureless than the first pitch; he pinched salt-grain-size quartzite crystals and stood on faint ripples in the rough, weathered granite, then executed a crux move involving a desperate lunge from razor-sharp side pulls the width of credit cards. Long had prevailed against overwhelming odds in completing his first free ascent, but the route had taken its toll.

“My fingers were a bloody mess by the time I finished that pitch,” Long said. “The nerves are permanently damaged. It could have ended my climbing career.”

By the end of April, even though the spring break crowds had abated, climbers were still pouring into Joshua Tree from everywhere. Germans, Brits, Aussies, French, Japanese, and Americans, among them a regular cast of characters you might read about in the magazines: Wolfgang Gullich, Jerry Moffatt, Patrick Edlinger, Hidetaka Suzuki, Jean-Baptiste Tribout, Stefan Glowacz, Kim Carrigan, Jonny Woodward, Russ Clune, Michael Freeman—not just kids on vacation but serious climbers living out of vans and rental cars with plans to travel for months at a time. They would hit all the hot spots to test themselves against the hardest routes America had to offer.

One day I set out with Clune, an East Coast climber on an extended trip out West, to work on Gunsmoke, a classic boulder problem that was a must-do on the Joshua Tree hardman circuit. There were a lot of climbers assembled around it, a veritable international gathering. I recognized two Germans, Stefan and Uli, who were in the next camp up the road from ours. Clune knew the Brit, Jonny Woodward, a gangly, bespectacled climber brimming with energy and enthusiasm. And then there was the Aussie, Geoff Weigand, every brash inch of him, calling everybody a “wanker” and saying generally derogatory things about everyone and everything.

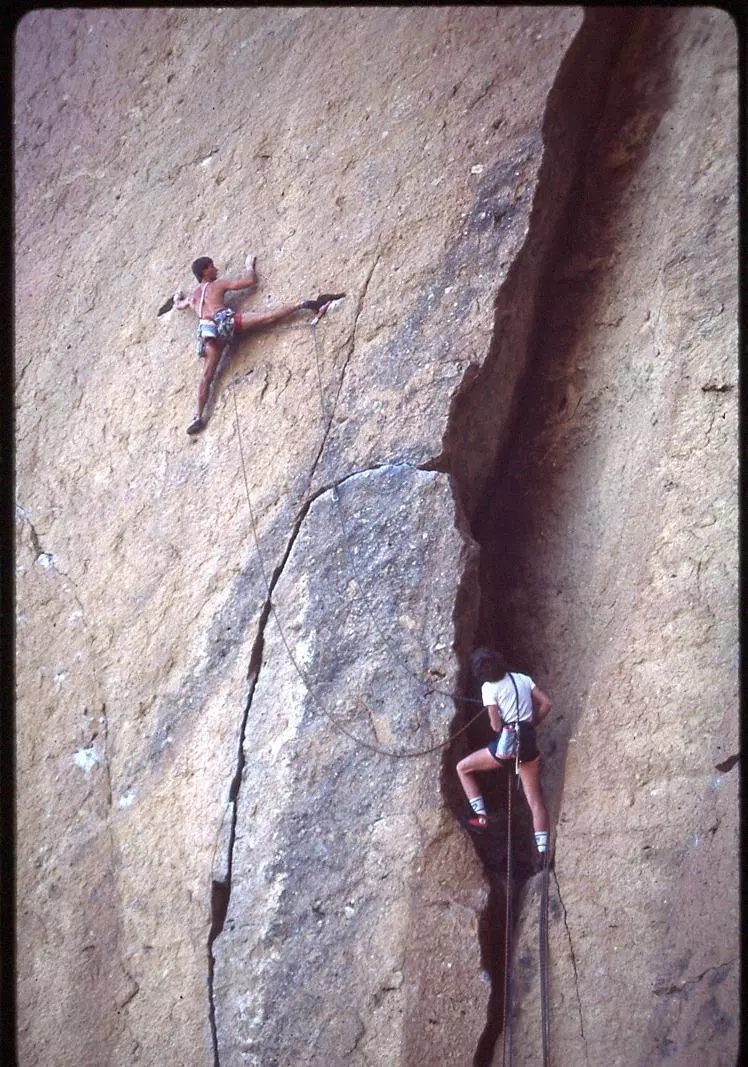

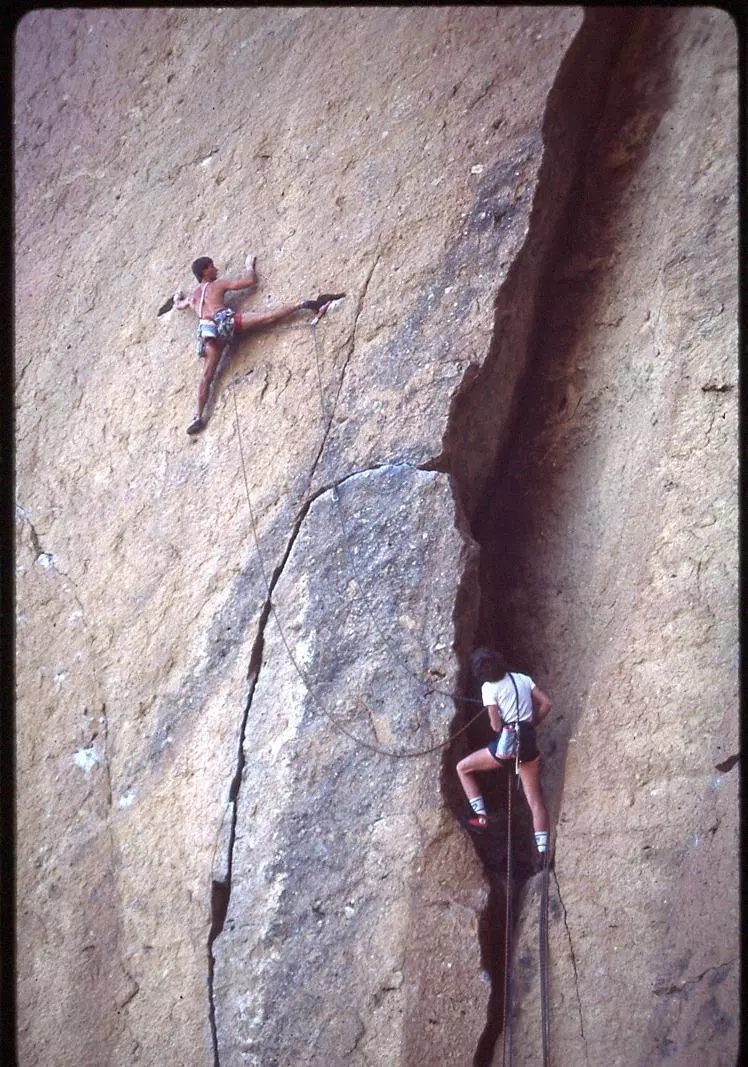

Geoff Weigand and Jonny Woodward on Slow Burn (5.12), Smith Rock, 1985.

The impromptu international climbers meet reconvened in our campsite that night, hosted by Todd, who within minutes was everyone’s new best friend. He showed off the Skinner Box and his workout setup, and peppered everyone with questions about the desperate routes they had done and those they planned to do. The presence of so many foreign climbers was something new and unexpected. I had come across the occasional stray Brit, German, or Japanese climber on previous trips, but now I was engulfed by a whole cast of them, all chatting amicably about their hard climbs back home and how they compared with those in the States. The consensus seemed to be that American climbers were pathetic by comparison, with the Brits and Australians being the most vocal about it, the Swiss and the Germans more diplomatic. But overall, the general impression was that their climbs back home were harder than anything in the States, and American climbers were lagging behind international standards.

This impression was reinforced by each new issue of Climbing, Mountain, and Rock & Ice, which included reports of yet another foreign climber tearing it up on American rock—an influx the climbing media dubbed “the Invasion of the Route Snatchers.” Jerry Moffatt, the self-proclaimed best rock climber in England, had on-sighted The Phoenix, Ray Jardine’s 5.13a testpiece in Yosemite, as well as Equinox, Bachar’s 5.12c thin crack in Joshua Tree, and he had easily repeated Psycho Roof and Genesis, nabbing the coveted second free ascents of two of Eldorado Canyon’s hardest routes. He added insult to injury by later toproping the latter in his running shoes. Wolfgang Gullich had repeated Grand Illusion, Tony Yaniro’s futuristic 5.13b/c roof crack at Sugarloaf in the Lake Tahoe region. He was the top German climber at the moment and probably the best climber in the world, considering his new route Punks in the Gym at Mount Arapiles was rated 32 on the Australian scale—the equivalent of 5.14a. Later in 1985, during a visit to Colorado, French climber Patrick Edlinger would on-sight Genesis, the 5.12c route Jim Collins had established in 1979 after more than fifty tries over several months, and he would also repeat several other hard routes with minimal falls, including Rainbow Wall, a rappel-bolted route in Eldorado Canyon regarded as Colorado’s first 5.13, and Sphinx Crack, a 5.13c crack in the South Platte region. Also visiting the States in 1985 was Kim Carrigan, the self-proclaimed best rock climber in Australia; in addition to repeating The Phoenix and Grand Illusion, he would establish several new first ascents that would upend the American climbing scene.

What was it, we wondered, that these foreign hotshots had that American climbers didn’t? How did they do it? What made them so good? We decided it was their can-do, no-holds-barred attitude about free climbing. They weren’t afraid to work routes on toprope before leading them free. They weren’t castigated if they hung on the rope while working out the moves. They weren’t vilified if they placed bolts on rappel. Also, the Europeans were batshit about training, climbing at least three hundred days each year. They bouldered for technique, did laps for mileage, and holed up indoors for daily hours-long workouts, which made them strong as hell—endless sets of pull-ups, Bachar ladder repetitions, and sessions on their campus boards (a new training apparatus we had only just heard about). They were fearless when it came to leading, even soloing; they didn’t balk at running it out, pushing through the pain. They had the physical and mental tools to succeed, and for the most part, the Americans didn’t. John Bachar and a few others did, maybe, but Bachar, unlike the foreign invaders, had a mental block: he was hung up on style and ethics; he had to do things the “right” way, which was, it seemed, the entirely wrong way if you wanted to climb the hardest routes.

Geoff Weigand had a much simpler answer. “It’s because you’re all wankers,” he informed us. “We’re just better than you are. Get over it.”

Jeff Smoot is a widely-published author and climber. His new book, Hangdog Days, is excerpted in this issue of The Writer's Workshop Review. Excerpted with permission from Hangdog Days: Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14 (Mountaineers Books, April 2019) by Jeff Smoot.” Purchase a copy

here.

|